Removing San Francisco’s Urbanity

No doubt the Sheraton bean-counters figured they could make more money turning the space to another “higher” use, like a spa or a high-end celebrity chef restaurant. And get a few million bucks for the Parrish painting at auction. Odd they would want to kill another restaurant space when they had one sitting empty in the southeast corner of the same property.The removal of Maxfield Parrish’s Pied Piper mural from the bar of the same name in the Sheraton Palace Hotel was another moment of loss. Another piece of San Francisco that belonged to my parents’ generation during and after World War II, and the trace I experienced, vanished overnight. Another huge corporation acting in its own short-term interests erased our urbanity.

In college, when we fell in love with abstract expressionist, pop, and conceptual artists, we disdained Parrish as sentimental. But we grew more expansive in middle age and liked the Piper’s big gulp martinis and manhattans and found ourselves celebrating an era before our own under Parrish’s slightly garish and beautifully rendered fairy tale. At least there was his mark.

So a group of cranky folks like your faithful correspondent started complaining. Petitions from change.org and stories in the local media appear to have pressured the Pied Piper owners to bring the painting back to the Palace. But they aren’t promising that it will be in the bar. If we had Facebook when corporate know-nothings tore down the City of Paris and the Fitzhugh Building, we might have a more urbane San Francisco—certainly a more beautiful Union Square (that renovation of the park a few years ago didn’t exactly help!).

Forgive me for getting sentimental about the San Francisco that isn’t. I just don’t want to lose the San Francisco of my childhood forever. This was a San Francisco built by individuals who tried their luck in gold fields, or sold to those who did, and then left their mark. But the gas ran out after a century or so, and the rich sold up to faceless corporations or closed shop. It’s getting harder and harder to find beauty or invention that hasn’t been folded into homogeneity. On this beautiful spring afternoon, we walked along Lakeshore Avenue near our home in Oakland. A beautiful old-fashioned neighborhood street that has been infiltrated with a Chipotle, Gap, Noah’s, and Starbucks. (We tend to forgive Peet’s because they were founded in Berkeley and lots of people knew the man, Alfred Peet.)

Lately I’ve been remembering downtown San Francisco as it was before the tide turned. I loved to go shopping as a kid and teenager because design and retail were connected and, although I didn’t know it then, linked to real people.

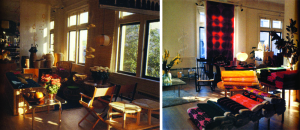

If there was a favorite shop, it was Design Research in Ghirardelli Square. A primer on good modern design. I used to fantasize that I lived in that store. Of course, hundreds of people contributed to this shared vision of architect Ben Thompson. There is a fine book by his widow Jane Thompson and design writer Alexandra Lange about the company and the San Francisco store.

I would still buy just about everything they sold! In the late 1960s, Thompson lost control, and over time the store lost its footing. Now the Ghirardelli tourist chocolate emporium has expanded into the downstairs space.

|

| Two shots of D/R San Francisco courtesy Chronicle Books. |

|

| Design Research: The Store That Brought Modern Living to American Homes © by Jane Thompson and Alexandra Lange Courtesy Chronicle Books |

The City of ParisSan Francisco’s most magnificent retail building and store was, of course, the City of Paris. Drawing on the design of belle époque retail stores in Paris, Felix Verdier created the finest department store in San Francisco for many generations. It was, in a way, like an early shopping mall, with several vendors selling their wares under one roof, a stained glass roof. In the stained glass roof was the image of the first store, the boat from France that brought goods during the Gold Rush, the Ville de Paris. Beneath the boat was the Latin phrase Fluctuat nec mergitur, which translates as “It floats and never sinks.” That very canopy still exists, somewhat ironically, at the top of the Neiman Marcus rotunda. The rotunda was mostly rebuilt when Neiman replaced the City of Paris store in the early 1980s with that very Texas monstrosity by Philip Johnson, the most chameleon-like of architects. Every year, a beautiful Christmas tree occupied the City of Paris rotunda, which was then located in the center of the store. Although Neiman puts up a tree in the reconstructed space every year, it looks more and more fake.

|

| Courtesy wikipedia.org |

The City of Paris demolition, along with the destruction of the Fitzhugh Building on the opposite corner of Union Square, galvanized the preservation community in San Francisco, and many other losses were prevented. But the city lost two anchors on its main outdoor room, and while Union Square prospered, much of its dignity was lost forever. The Saks Fifth Avenue that replaced the Fitzhugh grows blander with each passing year.

|

| Fitzhugh Building |

The other family-owned stores all vanished in the second half of the last century: the White House, Ransohoff’s, Livingston Bros., Joseph Magnin, and of course the crown jewel that lasted into the 90s, I. Magnin.

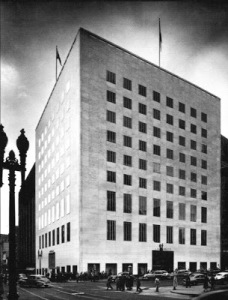

I. MagninAfter the City of Paris, my favorite big store was the I. Magnin at Geary and Stockton. By the 1940s, the store was no longer family owned. But it operated independently within the Federated empire until its closure. Also in the 1940s, architect Timothy Pflueger reclad the steel-framed Butler Building—which was under construction at the time of the 1906 earthquake—with a modernist marble façade that looks contemporary today. The air was perfumed, and a middle-class kid could feel posh for an hour or so. For many years, the men’s shop was on the right as you entered the main lobby. When I was a teenager, I loved going to the third floor and walking around the dress circle, where the exclusive women’s clothes were. The haughty sales ladies didn’t bother to say hello, knowing that I wasn’t shopping for my mother or a girlfriend! I didn’t want to be a fashion designer, but I liked the scale of the room, the light, the hush, and a few beautifully curated dresses and coats. Often I wondered what made them different, as I knew nothing about being a seamstress or the nature of fabric. But I was never thrown out, and I could make it my own kind of fantasy world. Then I would go downstairs and buy four bars of that beautiful lanolin soap (photo). The mother of my high school pal Susie Peterson turned me on to the lavender scent. When I. Magnin was closing in the early 1990s, I rushed out and bought several boxes of it. The last bar is now gone.

|

| I. Magnin relocated to its luxurious marble palace on Union Square in 1948 from and older facility. |

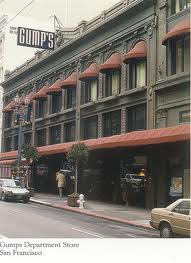

Gump’sWhen Gump’s moved from 248 Post Street eastward, the Asian-eclectic charm vanished. In the old store, I loved the interior decoration department upstairs and the famous jade room; occasionally the gallery had a good show. Around each corner was a surprise. The first floor on the left was reserved for the requisite tourist crap, but everything else had been selected with care. They used to sell those beautiful Palembang chairs that Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy had in their home, memorialized forever in David Hockney’s portraits. Another family vision that didn’t last long beyond the family.

|

| Old Gump’s |

|

| Don Bachardy; Christopher Isherwood by David Hockney Courtesy npg.org.uk |

EmporiumWe didn’t shop much at the Emporium, because its suburban branch, Capwell, had a large outpost at our local mall. It was a store for basics, not luxuries. But we did go to the Emporium for the rides on the roof at Christmas after visiting the City of Paris Christmas tree. Would any corporate bigwigs think of putting carnival rides on the roof of their department store in this age? Too much fun. Goes against the brand. Like the city of Paris, the Emporium also featured a central rotunda that was reconstructed when Westfield extended the San Francisco Centre mall behind the Emporium façade. It is odd to look up inside this modern mall and see a relic from the past, much like seeing the City of Paris rotunda preserved in its glass box. Historic elements have been reduced to odd fragments decorating the corporate hegemonic order. They are just political compromises.

TiffanyWhile Design Research represented casual modern design, Tiffany & Co., located in a narrow store on Grant Avenue in the ground floor of the former White House building, was a jewel box of haute modern. The décor was a collaboration of Tiffany design director Van Day Truex and decorator Billy Baldwin. Van Day Truex’s personal stamp was everywhere in the store. You opened the heavy brass doors and walked down a few steps of sisal carpeting into quiet chic with slipcovered love seats, white table lamps, Bielecky Brothers rattan chairs (adapted by Baldwin from a Jean-Michel Frank design), Parsons tables, and lacquered trolleys filled with beautiful small treasures. It was heaven. Where else did you get to sit down as if you were going to be served tea while your tiny Aalto vase was wrapped in a baby blue box as if it were a Rolex?

The new store on Union Square features a wonderful early Tiffany lamp in the stairway, but as in so many of these places, you can’t feel the individual hand. You can find the great Elsa Peretti, Paloma Picasso, or Frank Gehry designs, but you have to ask. It’s all vaguely luxurious and dull.

|

| One of Billy Baldwin’s most famous clients used his chairs for Tiffany in her contribution to The New Tiffany Table Settings. |

VC Morris Gift ShopSometimes change is good. I remember visiting, in high school, the Helga Howie boutique on Maiden Lane by Frank Lloyd Wright, his only building in the city. (He designed some houses outside of San Francisco and, of course, the Marin Civic Center.) When it opened at the VC Morris Gift Shop in 1948, Wright was playing with circular ramps, which would later find its fullest expression at the Guggenheim Museum. By the time I found the shop, Ms. Howie and her husband were selling fancy knitwear and were always courteous to this gawking high schooler. But I can’t say that a high-end dress store really worked in that space. For the last several years, the landmark has been home to an ethnic arts gallery, and it works beautifully for that purpose. There have been at least two significant alterations. The metal security gate compromises the original tunnel-like entrance. And the lights that were embedded in a circular pattern at the entrance are gone. But it’s still the retail gem of Union Square. Frank Lloyd Wright lives; his red chop is still there on the façade.

I don’t mind so many high-rises South of Market, but I do wish the folks who are converting the old phone company building on New Montgomery (again by Timothy Pflueger) would repair the terrible terra cotta work that was done in the last go-around. Instead of following the original brick-like pattern, they introduced a grid. We want to see the mark of the individual, but not if it’s wrong headed! Every day I walk around the city. I look for the sign that a person who cared about urbanity or beauty, whether it is an architect, designer, artist, artisan, chef, or bartender, is still at work holding up the value of the human individual’s contribution. Each time a faceless corporation removes the mark of a person, we lose something beyond the artifact itself.

I’m glad that those folks over at the Palace listened when people spoke up, and I do hope they put the mural back where it belongs. While we like the restored House of Shields saloon, all the hipsters there speak up rather too much, and we can’t hear ourselves!