Q: So much of your work is about distillation. And even though you’ve distilled it really far, there are multiple meanings to be found in the simplest of illustrations. Are they always intended, or are they sometimes a surprise because of your long history of doing this? Do you end up putting in layers even if you don’t know you are?

CF: I may very well do that. I never try to draw a picture of the exact thing.

Q: It’s an idea?

CF: It’s not necessarily an idea. I try to bring an idea to it. There are only a dozen or so repeating messages in corporate business anyway. My job is to symbolize a lot of those things, but leave enough room that everybody can see a little something in there. If it doesn’t communicate a central idea, then you’re getting into that fine art territory again. But I have a job to communicate some central message. The fun is in a lot of those nuances. Why do I draw buckets so much? Why do I draw hoses? I don’t really know. It’s just that some of those articles are the most fundamental tools that everybody understands. We understand how a bucket works. It’s a vessel that holds something. It’s got a handle. If you turn it sideways, something comes out. It’s that simple. It’s a great device for storytelling.

Occasionally, an art director will send me a sketch of something they want me to draw. They have usually studied my work so it looks something like what I might do. But because I didn’t go through the process of solving the problem, I can’t get behind doing the drawing. It’s not ego, it’s ownership of the story and why it’s the right answer to the problem. I have to go through that myself to evaluate whether it will be a good illustration or not. It’s not just a drawing problem. I get as much fun out of the sketching as I do finishing it. So much of my work is based on past work, it’s more than just using the same symbols. Clients have to understand that I want to bring them something they’ve never thought of. I tell them, “I live in this world. I’ve been drawing this for 20 years.”

I’m looking for something that I’ve never seen before, that I really want to draw. It’s just like—a guy who wrote an article on me, he called it Frazierville.

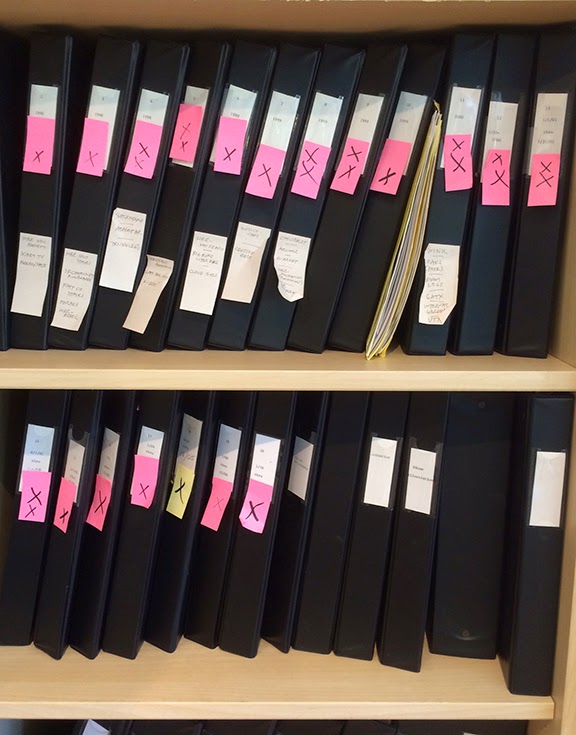

Q: What are those binders over there?

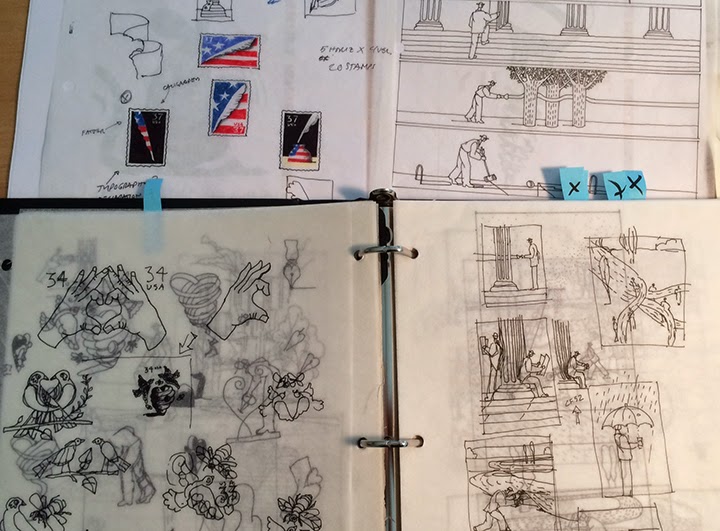

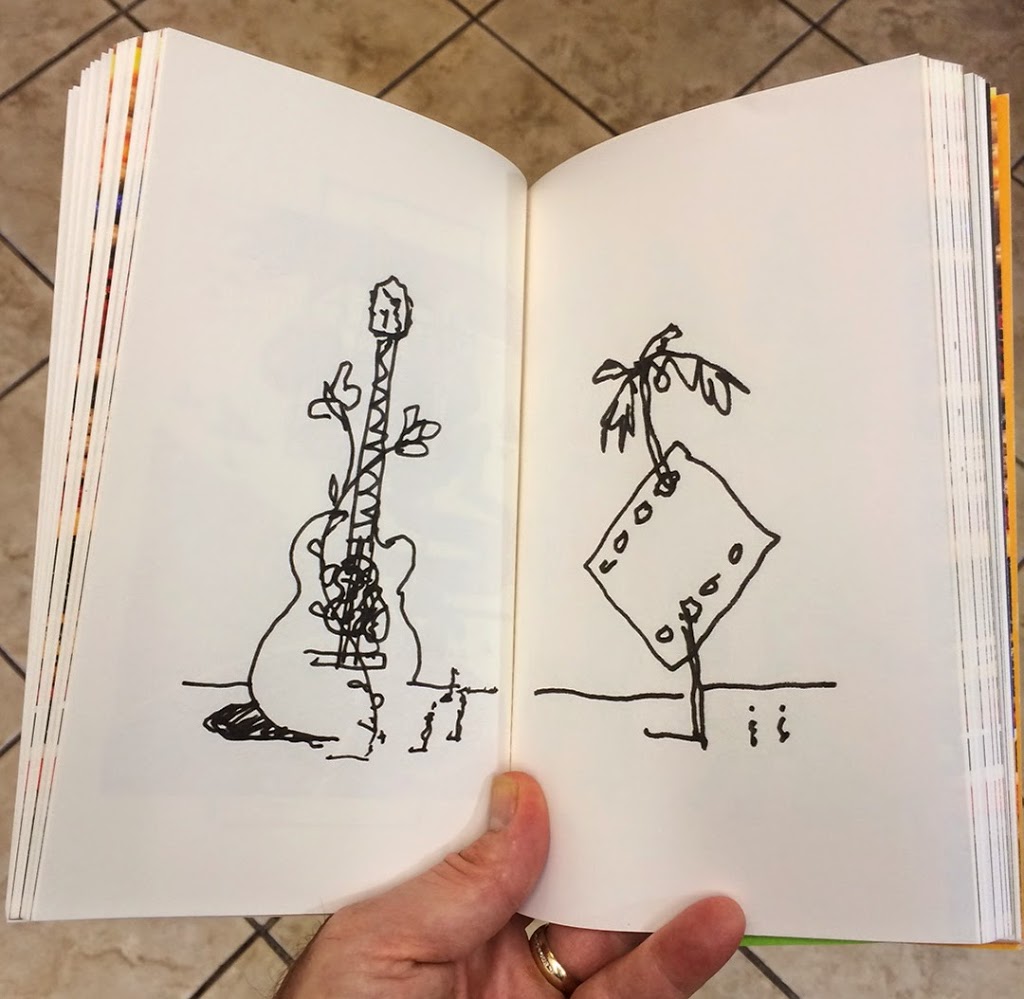

CF: The wall of binders are sketches. They are supposed to be chronological. I return to them from time to time. There are different levels of sketches. There are the real rough ones, and then I ultimately tighten up. Sometimes a drawing will be presented a few times to different clients. It’ll get rejected, and I’ll recycle it.

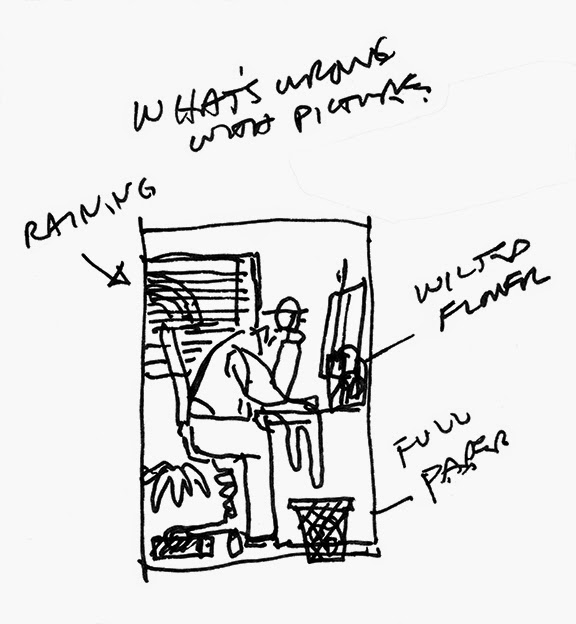

Q: Just like an architect. What is that image?

CF: It never got it produced. No client ever accepted it. I finished it myself. I do a lot of second rights licensing; I’ll sell something after the fact.

Q: How did they find that?

CF: I have a website, but sometimes a client will come to me and say, “Do you have anything that you’ve done that fits this message? We don’t want to pay for you to do a new one. We want to buy second rights to an illustration.” I also have lots of original illustrations that have never been licensed.

You just want to live in this world and try to improve it. And when I say “improve it,” for me it’s about finding essential elements and—“truths” isn’t quite the right word—but possibilities. It’s only until I’ve drawn something like, say, water a number of times that I get very familiar with it, and I get comfortable with it, and comfortable with rendering it a particular way.

Q: So sometimes you’re doing the practice without knowing the outcome, because you have faith in the process? The client didn’t go for it, but it’s a great idea, so you decide to take it to a level of completion so it advances what you’re doing in the world, even though you may never be paid.

CF: Exactly.

Q: It seems almost Buddhist. I wanted to talk about technology and the production of your work. You withdrew from graphic design about the time it became really automated.

CF: Yeah. We were finishing all the work on computers. Since then it’s only gotten easier. The problem today is everybody’s a graphic designer.

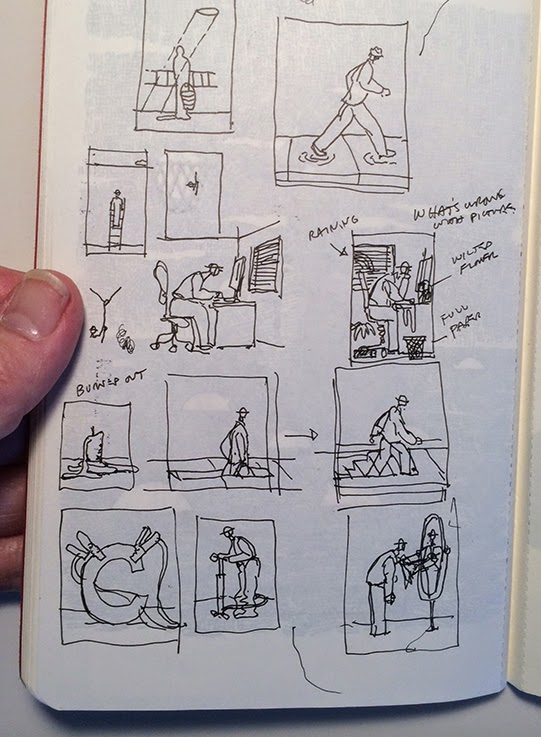

Q: But how do you physically make these illustrations? I see the first part—the first rough sketch—and then you refine it. Then what happens?

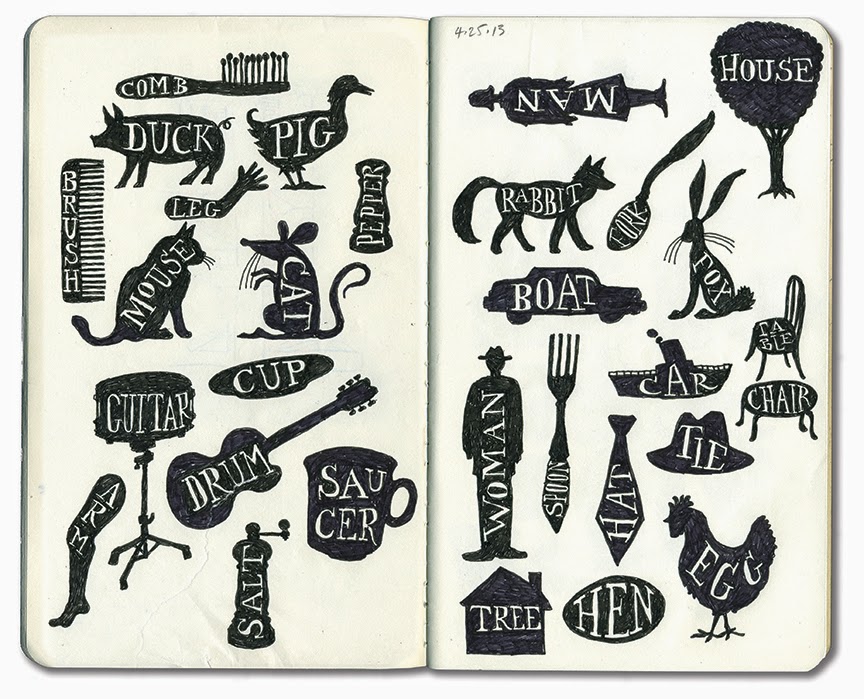

CF: Okay, I’m going to show you how primitive my methods are. I draw with a pen, and I draw with the same pen, and I have forever. Although I switched from a Pilot pen to a Micron about six years ago, and I love these Microns. And I draw really small. Part of that is because I can get a lot of things on a paper. I can draw very quickly.

One of the things about solving problems, whether you’re a designer or an illustrator, is you have got to keep yourself from getting frustrated. The hardest part of our job is when we start to feel a sense of failing. When we’re in the process of solving the problem, you’re going, “This is not fucking working. I am shit. I am the worst designer in the world. Oh no, my career is over.”

Q: As in, “Are they going to take back the car, the house?

CF: You cannot let that happen. You have to work quickly and be able to abandon something that is shit and go on. You just to keep drawing and don’t judge it. Do that later. I’ll judge it in an hour. I’ll judge it tomorrow. I’m not going to judge it right now. Just keep drawing little ideas, because that morning-after test is always better than that moment. The name of the game is to invest as little as possible in ideas so it doesn’t hurt that bad when you toss them. But you’ve got to keep moving, which keeps you from stopping, and sitting there, and going, “Is this shit?”

When I started in design at that first job in Palo Alto, my boss had this thing over his desk that said, “You can’t polish a horse turd.” I’ll never forget that. All the work you put into it is not really going to improve it if it’s just not a fundamentally good idea. I’m always looking for an idea that’s worth spending time on, and I’ve learned to see that with a doodle. I could tell you almost by describing it to you.

Now, the other reason to work small is that compositionally I’ve resolved a lot of the issues already. I’ve already built in scale. As you start to draw something big, it’s hard for you to see all those relationships that well. So that starts to also define a vocabulary. Because it’s so small, I’m not going to put many details in it. It’s not interesting to me. Next, I cut this the illustration out of Amberlith—a masking film used originally for silkscreening. Then I scan it. All I need is an orthochromatic form. Because I’m going to color it in the computer.

Q: Where do you still get Amberlith?

CF: It comes in a sheet. I just found the last roll of it in America.

Q: What are you going to do when this material runs out?

CF: I’ll retire. The last roll I got is 30 feet, so I’ve got plenty—I’m good.

Q: You use old and new technologies.

CF: People think I build these illustrations in Adobe Illustrator. I do sometimes, usually not.

Q: God, you must be mad.

CF: What happens is it creates its own vocabulary. I want you to look at it and go, “This was made by hand.” I want happy accidents. I’m interested in that little bit of character that takes place. The other element to this is that it forces me to edit my level of detail. These characters don’t have eyes because they’re too friggin’ small to draw! I don’t want you to care about him that much.

Q: Technology has also changed who you do work for. There are fewer print publications. I hear it’s stabilized somewhat, but it certainly has been on a downward trajectory. There are probably fewer annual reports. How has that affected you?

CF: It used to be when we’d write a contract, it would be for print, and they’d say, “And maybe some additional web usage.” It’s the other way around now. It’s web usage, and maybe a little print.

Q: Do clients hire you for digital projects?

CF: Yes. Ultimately everything will be on a digital platform.

Q: Are there days when there isn’t an assignment and there are ideas that you want to explore?

CF: Of course, that’s the only way to bear those times.

Q: Are you being pulled towards noncommissioned work?

CF: I am being pulled towards trying to create projects for myself. You’re going to back me into this artist thing, I know.

Q: I usually end where I start.

CF: Part of it is trying to invent some things that I can sell. I don’t want to change my style. But I do have some more ideas, and so I’m always trying things in my sketchbooks. I got called to jury duty, and I was doing these “opposite” silhouettes waiting for jury duty. As you know, I have this other venue—children’s books. That’s where I jump to when I’m not doing a commissioned assignment, because I always have a book that’s supposed to be getting done—or I’m developing.

Q: What have you worked on recently?

CF: I did a large design/illustration project for Goodwill, which involved designing their fleet of 50 trucks for the Bay Area. Did a logo for a fine knife maker named Wilburn Forge. I’m wrapping up a new kid’s book about these animals that are contagiously grumpy on the bus. Kind of like riding Muni I suppose, or any other bus in America. It’s full of good lessons for kids and parents and maybe a few laughs on the way.

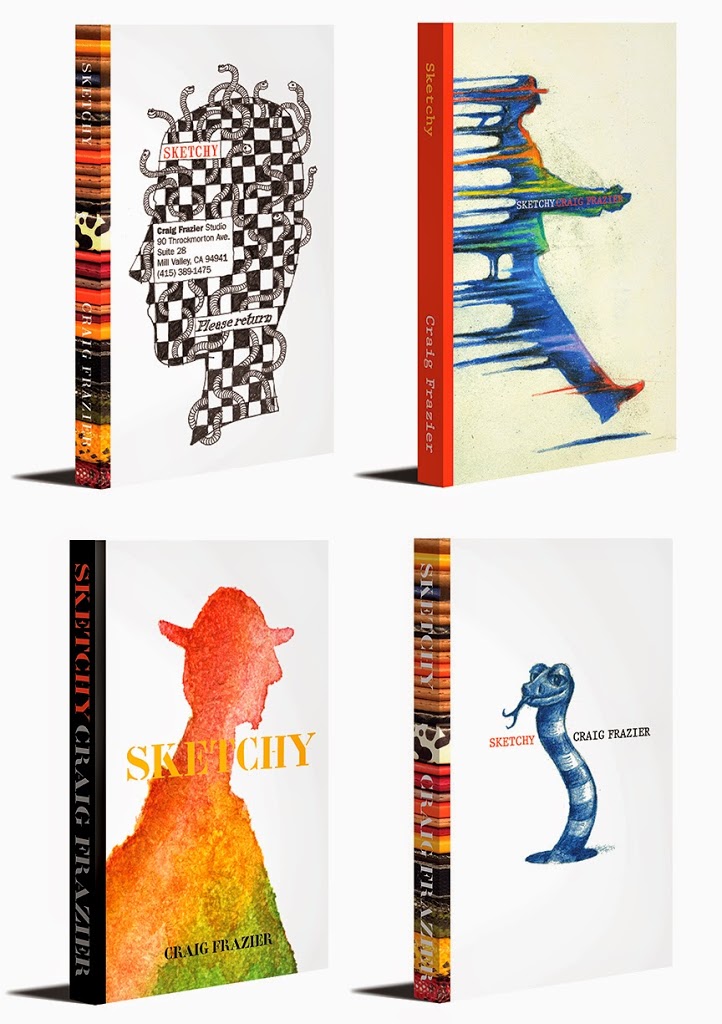

Oh, and I’m designing a book titled Sketchy that catalogs a lot of my sketches over the past 15 years that will parallel a show of sketches and process at the Savannah School of Art and Design this fall. It’s a collaboration with Mohawk Fine Papers and Xerox. It’s almost 200 pages and 30 different covers! I’m in the throes of finishing production on both due out in a few weeks. I better get back to work.

|

| Goodwill |

For more information:

http://craigfrazier.com/

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Craig-Frazier-Studio/413048848707075