Craig Frazier is an illustrator. Most of his work is by commission. But when you look at his collected work, it feels like the oeuvre of an observant illustrator/writer/artist. You enter what a friend of his calls “Frazierville.” I met Craig at a benefit for Oxbow School and decided immediately that I wanted to find out more about his process. Although I interviewed him shortly thereafter, it took me a while to edit the transcript. But since his work is timeless, I hope the delay isn’t a bad thing. He has a new book coming out entitled “Sketchy.”

Q: I want to talk about this continuum from graphic design—which is generally perceived as a commercial craft—to something called illustration—which is sort of commercial—to art. I interviewed Maira Kalman recently, and she said that she does not call herself an artist. She calls herself an illustrator. In order to work, she needs an assignment.

Craig Frazier: I am not a fine artist; I’m in total agreement with Maira.

Q: But what are you doing up in your studio at Sea Ranch?

CF: I’m upstairs doing the same work I do in my Mill Valley studio (though under very serene conditions), and my wife is downstairs making copperplate etchings. Now, that’s not to say that she won’t let me down there to make prints, but it’s really her studio where she makes her art. I’m a complete novice at printmaking—she, on the other hand, knows what she is doing. I learned about printmaking four years ago up at Oxbow during their summer program. Suz had been doing it for four or five years previous to that.

Copperplate etching is very humbling. I understand the beginning, middle, and end of all my illustration processes, but printmaking is a process that has a mind of its own—and also a beautiful mind if you want to get on board with it and let it take you somewhere. I’m not used to doing that. I’m used to being in charge. And copperplates don’t let you be in charge. The press is going to do what it’s got to do, and the paper’s going to do whatever it wants to do. You might rein that in a little bit, but you better be prepared to accept some errors and some turns in the road. It was in my fourth year that I finally started to surrender to it, and accept mistakes, and appreciate them, and say, “This is OK”—and quit drawing pictures like I do as an illustrator.

Copperplate etching is very humbling. I understand the beginning, middle, and end of all my illustration processes, but printmaking is a process that has a mind of its own—and also a beautiful mind if you want to get on board with it and let it take you somewhere. I’m not used to doing that. I’m used to being in charge. And copperplates don’t let you be in charge. The press is going to do what it’s got to do, and the paper’s going to do whatever it wants to do. You might rein that in a little bit, but you better be prepared to accept some errors and some turns in the road. It was in my fourth year that I finally started to surrender to it, and accept mistakes, and appreciate them, and say, “This is OK”—and quit drawing pictures like I do as an illustrator.

The difference between a designer or an illustrator and a fine artist is that a designer or an illustrator has an assignment, and they are supposed to be communicating; they are supposed to be solving a problem for a client within a set of parameters and objectives. That is the job, and the job isn’t done until you’ve done that, and the measure of that job is how well or poorly it communicates.

That’s measurable to some degree, whether you’re branding a company or you’re trying to illustrate an article. Fine artists have personal criteria. They do not have a client. In essence, there are no real assignments. They do whatever they want to do, which I think is a tougher assignment than working against a brief or illustrating a story.

Q: Because the whole world is possible?

CF: When do you know when you’re done? When do you know if you’ve done a good job? How do you know if you like it? With an assignment, I look at it and say, “Well, did I satisfy what I was supposed to do for a client? Did they accept it in the end? Did it go to print.” Job over, done.

You don’t have to sell it later on. It doesn’t have to measure up to public opinion. The hard part of being a designer or an illustrator is getting the assignment. Doing it is just the work that you do. But once you’ve got an assignment, it’s pretty much assured you’re going to get paid. A fine artist does something with no assurance that they’re going to get paid. In terms of a job, that’s a brutal existence. Most of us who have grown up in the working class—we like to get paid for what we do.

I’ve tried to stay clear of using “art” in terms of my definition of what I do. Maybe someday in the end of my life, when these things don’t matter and my income doesn’t matter, I can try to do that. But I think it’s going to be very hard to wring the designer out of me, which is going to make it really hard to be a fine artist, because I am assignment-oriented. The other thing is that I’m really oriented toward communicating. You can always tell an illustrator who has tried to leave that profession to become a fine artist, because you see pictures that look like something. They tend to be expressive.

So in your continuum—the three stages of my career that you were asking about—we’ll go back to the design one. When I was in college, I was studying to be a graphic designer. What I knew about being a graphic designer was that it involved some kind of applied art. I’d drawn all my life, so I thought, maybe I could make a living here.

Q: Where did you go to school?

CF: I went to Chico State, not a fancy art school. I just went up there to go to college and didn’t know what I was going to study.

Q: Did you grow up in the Bay Area?

CF: I was living in Livermore at the time.

Q: So Chico looked good?

CF: Yeah, really good. Unlike my own kids, I chose a college that was pretty close to the town I was living in. I went 200 miles north because many of my friends went there.

In my third year, my mom said, “Hey, have you heard about this thing, graphic design? You’re always drawing.” “No, never even heard of it.” “Well, that’s how logos get made. That’s how brochures are made.” So I took my first class and just fell in love with it. There was an assignment, and it was like something I was trying to fix. My dad was a mechanical engineer in the Air Force, and the one thing that he taught me was how to fix things. I worked on all my bikes, worked on all my cars, and I learned how to fix stuff. He was a designer and designed things he couldn’t really talk about—because he worked for the Department of Defense.

He was always drawing on envelopes and figuring stuff out, and so I probably got a little bit of that genetically, and then it was also just training. It’s like, “Hey, if it’s broken, Craig, we’re not buying a new one. We’re gonna fix it.” If you’re Scottish, you fix, don’t replace!

I declared a graphic design major, and in my second year in the program, I took my first illustration course.

After taking a number of illustration classes, I thought, “I want to be an illustrator. That’s really what I want to do.” I left school with an illustration portfolio. The first two people who looked at my portfolio said, “You shouldn’t be an illustrator. You should be a designer. I said, “Okay.” So I went to Palo Alto. This is 1980. I landed a job right away and was really lucky. Silicon Valley was just starting.

Q: At a graphic design firm?

CF: Yes. I walked in, and the owner said, “We have a position.” They had just started the firm. “The reason I’m going to hire you is because you can draw.” Because in those days, long before we had computers and long before people were swiping stock photos and images, you always drew your prototype designs.

So I became a graphic designer, and learned production, went through the mentoring program. Within two years, I started my own firm, in San Francisco.

Q: Did you have a client?

CF: It was a management consulting firm that launched us. That set us off, and we had an office on Union Square, right across from Neiman Marcus. I started getting work with an ad agency—Saatchi & Saatchi—started to be kind of a ghost designer for them. We eventually moved off to South of Market.

By then Silicon Valley had burst open, and I was driving all the time to Palo Alto or farther to do work for tech companies. I also had the San Francisco Opera and San Francisco Ballet as clients. Then we also started doing a lot of work for Steelcase. That got me into the furniture business, and lead to doing work with Herman Miller and with Agnes Bourne.

That was really great work. It was fun because it was design-oriented, and they were smart people. If I could go back to that, I probably would. That was a nice niche. Then we got a lot of technology work. We had this client, Trimble Navigation, which is still around. They were the founders of GPS technology, which was originally developed for the nautical industry. You could get a GPS unit for $3,000. Now it’s on your phone. [Laughter] We took that company public and helped popularize GPS technology.

I was learning how to impact companies and be a part of their communication and help them grow. I was spending most of my time doing proposals, and I’d come back and I’d design at night—and I had four or five employees. But control freak that I am, I always designed everything. I would do sketches, thumbnails, turn them over to an assistant, and she would put it together. I would direct all the photo shoots, and the writing, and do all the selling. I experimented with getting people to help sell for me. It was tough, and that never worked out. They can’t do it. They didn’t care about the same things that I did.

|

| Steelcase Ad |

|

| Trimble Ad |

Q: It’s got to be the professional. When I talk to architects, I’m always saying, “If you can’t do this, then it’s not gonna work.” Because it comes down to the architect connecting with the client.

CF: Yeah. You’ve got to convince somebody to trust you. Whether they understand what you’re doing or not, they’re going to have to trust you. I kept thinking, “How do I get out of this business? I can’t stand it.” We were doing great work, and had a good reputation, won AIGA Awards and all that stuff. My kids were little, and I’d just come home—I was so tired and cranky, because I was selling all the time. If you have any anxiety—and I do—you go into a meeting and you think, “God, this is going to go one of two ways. It’s going to go really good or it’s going to go really bad.” It never kind of went in between. It’s like, this could explode if the wrong person came in the room.

I remember thinking, “How do I get out of this?” I told my wife, “I’d sure love to be an illustrator. I’d love to work in some little office overlooking a downtown somewhere.” What would that be like, being an illustrator, where you’re just drawing by yourself? You don’t have to do these meetings. You don’t have to put on a suit and tie. So I learned a little more about illustration and who illustrators were. I knew who Milton Glaser and Seymour Chwast were, and I had hired a few illustrators.

I was getting burned out in design. I thought, “I need something more personal here.” In those days, with graphic design, you were supposed to be stylistically neutral. You were not supposed to assert a point of view. You could have a point of view about the way you treated a page, but that company’s identity was their identity, not your identity, not your style.

Q: You weren’t really even interpreting it very much, were you?

CF: No. Of course, everybody ends up having their own kind of a thing. Some people are very ornate, and some people only use Helvetica, but you’re supposed to give a client a choice: “We can make things very Swiss, or we can use Garamond.” Those decisions are not just about type, but a company’s image. You owe that to them to try to decide where they land in that spectrum. I always felt like I couldn’t impose myself. Take someone like Michael Vanderbyl, who is a brilliant design stylist, in my opinion. He has marketed his style to companies—much like an illustrator does.

Q: You want it or you don’t.

CF: Exactly. I wasn’t that way as a designer. I look back, and I think I had a great career and did good work. But I didn’t feel that strongly about graphic design. I thought, “Well, how can I get out of this?” I wanted to relieve that stress. The other really important thing was I observed was that whenever we were going to do an annual report, we would hire a photographer, and he would get a lot of the money and the recognition.

I thought, “I want that part of it,” because, in part, I had to sell him. He didn’t have to go to the meetings, I did. “I want to be in those shoes. I want to be sitting in my studio, making my stuff, and people are out there selling me.” So I said, “I’m going to take a swing at this.” And I started doing some drawings in my own projects.

Q: It was for annual reports?

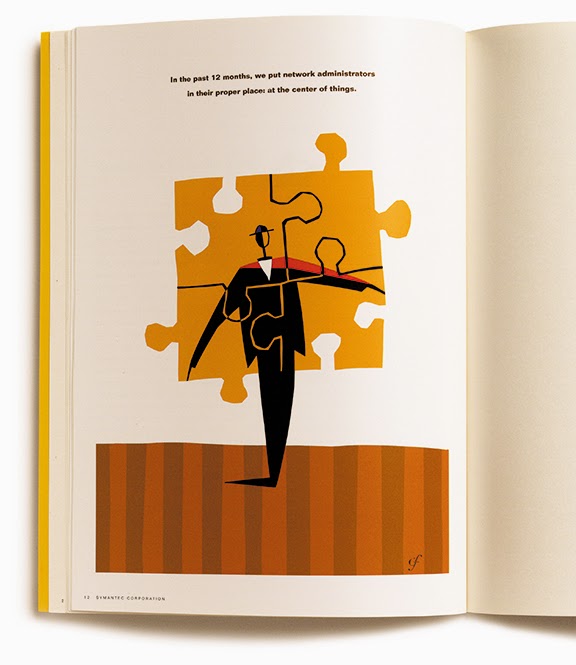

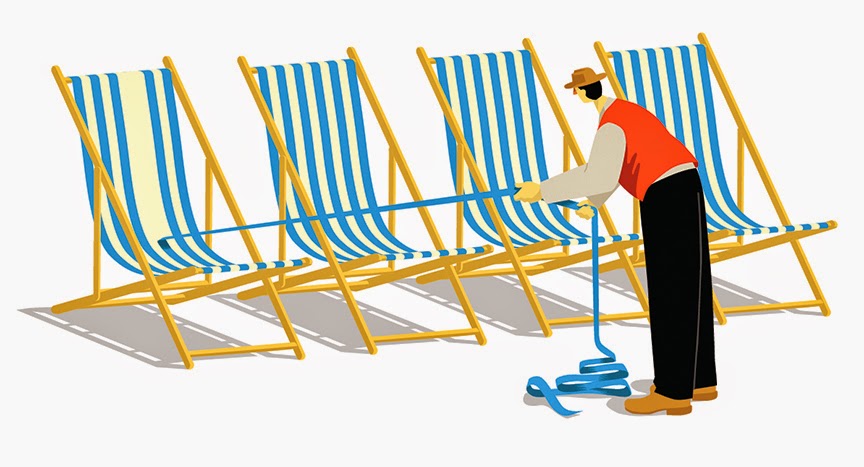

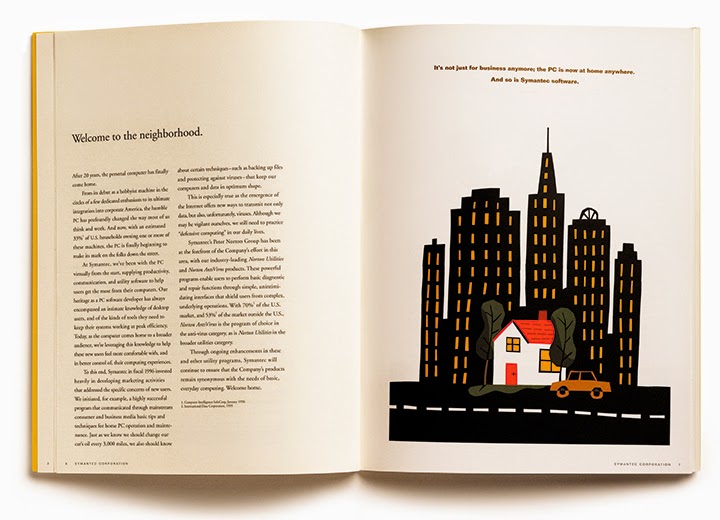

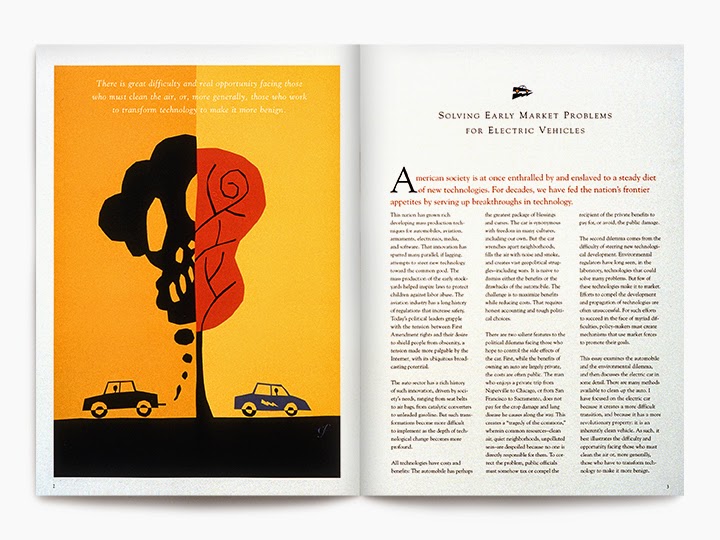

CF: Yes. One was for the Energy Foundation in San Francisco. Another one was for Symantec. And another one was for Oracle. I didn’t tell them who was doing the illustrations.

|

| Symantec |

|

| Energy Foundation |

Q: But you put forward the idea that you would do it with illustrations rather than photos?

CF: Exactly. Nobody in the west did that. I was testing the water to see if I could start to make some work. I wanted to eventually get out of the design part of the equation.

So I made a little 16-page booklet of some of my illustrations. Some of it had been published, and some of it was unpublished. I sent out a thousand across the country to designers and to magazines. And the phone began to ring.

Q: Was it a self-published little book?

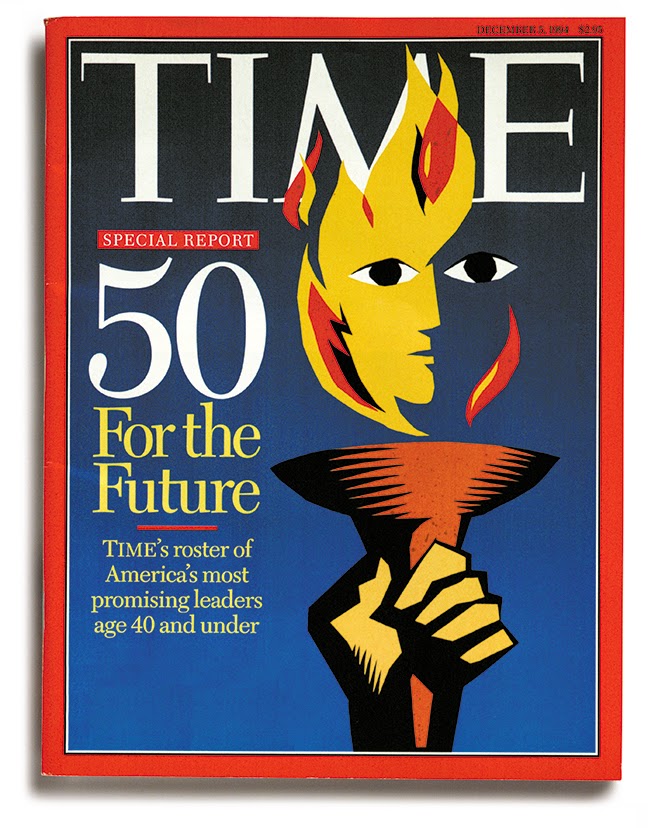

CF: It cost me $5,000. I got a large project in town for Pac Bell—one of the phone companies. I said, “This is working.” Then I got a cover for Time magazine. Then I got an Atlantic Monthly cover.

So I decided to close the shop down. I felt it could work. It took nine months to make that full transition.

I wrote a letter to my friends in the design community. I said, “Look, no midlife crisis, no divorce, no illness, just changing what I’m doing—no problems here, okay.” I said, “I will be illustrating quietly above Peet’s Coffee in Mill Valley.” It was an enormous relief, to make the change. I really wasn’t that worried about whether it was going to work. I told my wife, “I’m going to make less money.” And she was behind me, because apparently I was pretty cranky at that point! The pressure was clearly killing me.

Just before I closed up shop, one of the first things I did was the Mill Valley Film Festival poster, which was a breakthrough for me. I was asked to do it. I thought, “Okay you’ve got to have a style, Craig, and you’ve got to get known for it.” That’s the name of the game in illustration. It’s all style.

“I’m going to do this graphic thing,” I told myself, because that’s something I could do. I couldn’t paint—still don’t paint. I was learning how to communicate and how to get an idea inside of an illustration—a singular idea.

I asked myself, “What’s the one notion going on here? How pared down can we get it?” For the Mill Valley Film Festival poster, for instance, I put strips of film over Adam and Eve’s privates. That’s the joke. That’s the whole thing. When I started to get a few of those projects under my belt, I started to understand myself—that that’s what was interesting to me—the tone of that joke, how loud, how quiet—and the timing of it. There is timing on paper, believe it or not.

Q: How many sketches do you show a client?

CF: I show them two or three.

Q: If the client is really sweet.

CF: As a designer, I thought much more absolutely about solutions than now. That was just naiveté. But I liberated myself from that by realizing, “Hey, there’s a bunch of ideas.” It doesn’t mean that you show everything, but what if you have two ideas? What if you have three? We all love the privilege of choice.

But with options come conditions. “Here are the rules. I will give you three sketches for every illustration, but there’s no mixing or matching, and you have to pick one. The actual representation of things is not open for discussion. I’m not making the head bigger. I’m not putting eyes on it. You see what my work looks like, and that’s what it is.” I didn’t want clients directing the style I was trying to create—and they probably would if I asked them.

I submit them the same way I do today. I scan them, but they are just black and white, no tone, no color, because the idea is there and they can see it. They can see how I color. There isn’t any discussion about color, because that’s highly subjective. They have to trust me. But for every three sketches I’d show them, I would do a dozen of my own.

In Part Two, Craig talks more about his process.