The Strange Journey of Jacqueline Johnson’s Neutra Cottage in Los Altos

You can’t go home again. Sawing up and moving a historic house for eventual public use without taxpayer support is bound to be a little problematic. In the case of the Jacqueline Johnson house, one of three small cottages designed together by Richard Neutra, the surgery was a success, but it seems that the patient may have died.

Sure enough, there is a small renovated structure in the form of the original Neutra house, standing proudly on a busy street next to an existing community center. But it is not located in a place resembling its original placement in an orchard and very little of its original fabric was retained. One significant preservation issue in modernist structures is that the materials were often experimental and they fail or, in some cases, age beyond repair. But here the renovation substantially changed the original layout and purpose of the rooms and did not replicate the original building orientation. The little 750 square foot one bedroom cottage is now a small conference center with a new kitchen and bathroom available for community use. There is little clue as to the original use of each interior space despite a public video. I didn’t see any old fashioned floor plan, site plan, or historic photos when I attended the rededication in October. Perhaps that will be remedied with time.

Neutra house under reconstruction. Photo: Miltiades Mandros

Carport with two un-Neutra like posts. Photo: Miltiades Mandros

Indeed, this is a house that was literally torn apart by the fight for its preservation. Architectural designer Miltiades Mandros found the one bedroom house and a small studio behind a bamboo hedge in Los Altos when conducting research on Neutra houses in Northern California in 1999. The little cottage originally had a twin on the same site but it was destroyed and the lot subdivided many years ago. The original three structures were culturally significant because they represented an unusual commission in the Neutra oeuvre, a small very modest communal arrangement for a group of writer friends associated with Stanford University. One of them, the poet Jacqueline Johnson, went on to marry the well known painter, Gordon Onslow Ford. (Together they later commissioned noted Bay Area architect Warren Callister to design their home in Inverness.) It was Johnson’s modest bungalow that somehow survived.

The house’s recent owner, John Gusto, asked Mandros to design an addition to the Johnson cottage, which the city’s historical commission did not approve. Unable to expand the house, Gusto decided to sell the property. He and Mandros tried to find buyers who might save the modest house and relocate it. Eventually, a deal was worked out whereby Gusto donated the house to the Los Altos Foundation who would move the structure to land owned by the city. Los Altos Historic Commission member Justin Drewes championed the idea of the city donating the land for the project.

What happened next gets a little murky.The city was not willing to pay for the restoration of the modernist cottage beyond providing the vacant parcel of land.The fight for the little Neutra might have ended when the city said they had no money, but a few vocal citizens, including someone named King Lear, rallied to save the house.Without any government funding the local citizenry had to raise all of the money to relocate and renovate the house. At some point a decision was made to alter the house so that it could function as a community center.Restoration became adaptive reuse.

Citizens enjoying the patio. Photo: Miltiades Mandros

There is little substantive information on the Neutra House Project website about the restoration process.According to Mandros, who has followed the project for many years, there is some original siding remaining but little else. According to Lear, one of the community leaders and advocates of the renovation, some corrections are being made based on recent reviews from Dion Neutra, Richard Neutra’s architect son, as well as the Neutra scholar Barbara Lamprecht.

Apparently, there is no architect of record for the project and no historian or conservator was hired. That is not to say that the grass roots efforts were not well intended. Small suburban communities, even affluent ones like Los Altos, are just beginning to recognize the cultural value of mid-century cultural resources, but often they are not willing or able to secure government funds to preserve those resources. One advantage of government subsidy is oversight and hopefully, a process that follows the Secretary of Interior Standards for Historic Preservation.

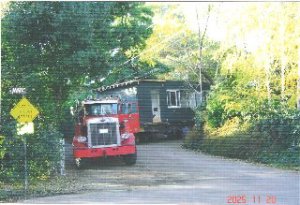

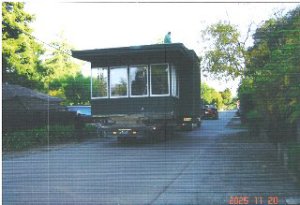

The house before it was moved. Photo: Miltiades Mandros.

The cottage being relocated. Photos: John Gusto.

But the result here is not preservation, nor does it tell us much about the early thinking of Richard Neutra.What we have is a reproduction of an exterior of a portion of a modest compound that Neutra designed in 1935.The profound lessons for other relatively young suburban townships are not found in the reconstruction of the exterior of this house, but in the strange process of trying to save this landmark.To preserve modernist landmarks communities need a paid architect, historian, and conservator.To hire those professionals a town needs the financial support of the city fathers and mothers.Maybe this new era brings more possibility about government support; maybe we can preserve more than the simple outlines of a modernist treasure.