Alcatraz is full of myths. Some true, some false. The park service has done a good job of underplaying the dramatic potential and introducing some interpretation, but not too much. Even so, the voices of birds on the ferry’s loudspeakers, the audio phones, the introductory materials, and the large crowds make it difficult to experience this solemn place as more than a quick trip between Fisherman’s Wharf and the highbrow shopping emporium at the Ferry Building. Is it possible to slow this experience down?

Ai Weiwei’s show “@Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz” is probably not going to mean a great deal to first-time visitors looking for Al Capone’s cell, the hospital room where Birdman of Alcatraz stayed, or the answer to how a trio of prisoners escaped through the ventilation system. But for return visitors, Ai Weiwei’s installation offers a chance to interact with several different kinds of spaces and experience a deeper insight into the meaning of freedom.

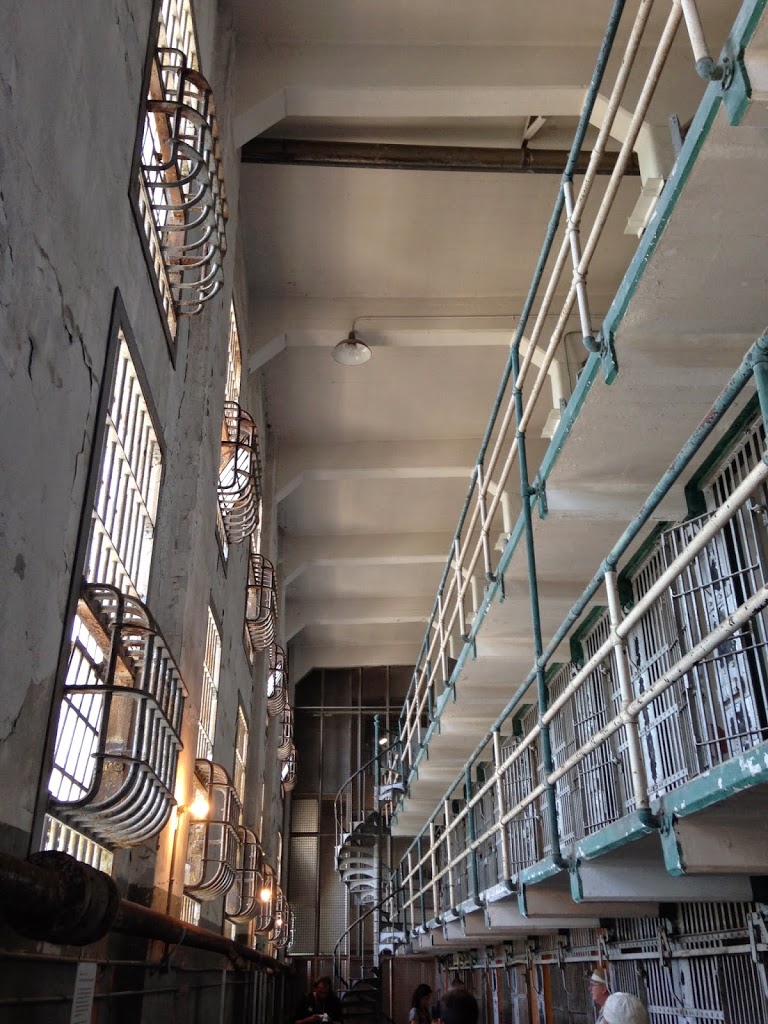

The New Industries Building has not been open to the public previously. This factory structure offers vistas of the bay and the Golden Gate, which the prison blocks do not. Prisoners had only endless days in tiny cells, so factory work offered variety to an otherwise monotonous routine. Above the prisoners was a gun gallery with armed guards ready to shoot if a whistle’s shrill was heard from the factory floor. In this spare building, the artist has created three large-scale but very different works.

With Wind is the first piece after the beautiful uphill walk from the ferry dock. Wind, a force that cools you in the heat, also makes a kite soar in the sky. The beautifully detailed dragon is not frightening, nor is it alive—like any prisoner, it is waiting for an unseen force. A viewer can look at the beautifully detailed structure and painting, but I found myself concentrating on the sharp contrast with the ugly peeling workplace where prisoners and their guards toiled, counting days to release of one kind or another. Another view of this cloth serpentine-like form can be seen from the upstairs gun gallery. This narrow space, barely wide enough for two to pass, was filled with sunlight on the day I visited but felt unbearably claustrophobic. I couldn’t focus on the work again until I left the building. It is no mistake that Ai Weiwei chose a dragon kite, a stereotypical Chinese icon, to begin his complex and enormous multimedia essay on freedom.

|

| Trace, 2014 photos: Kenneth Caldwell |

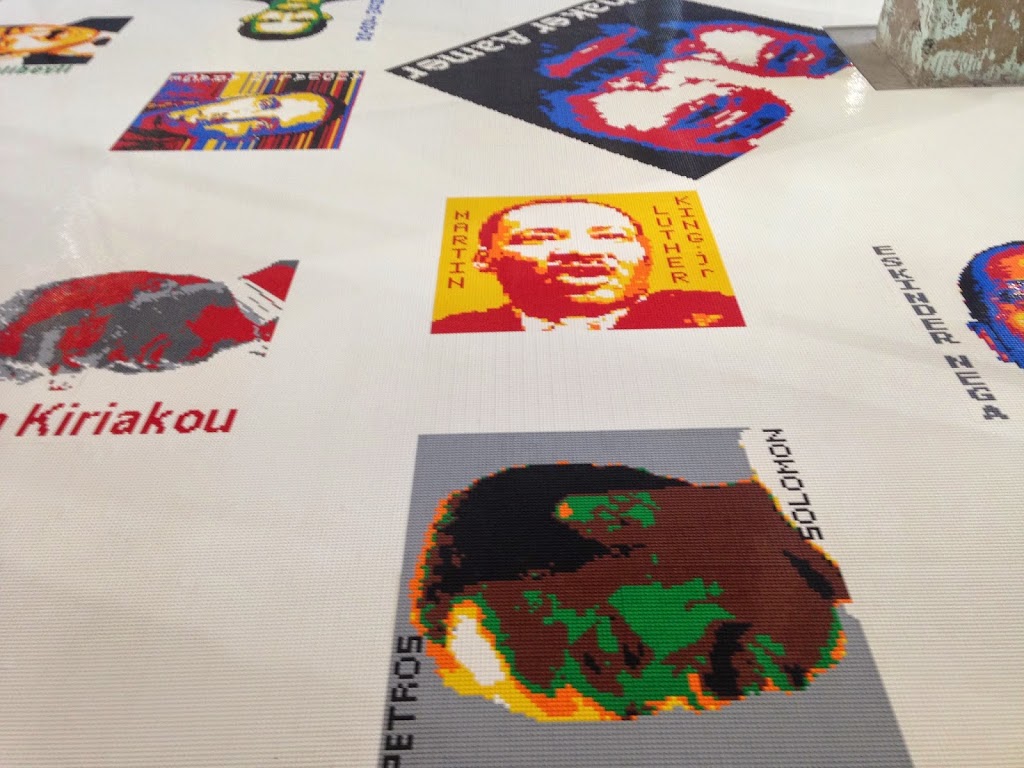

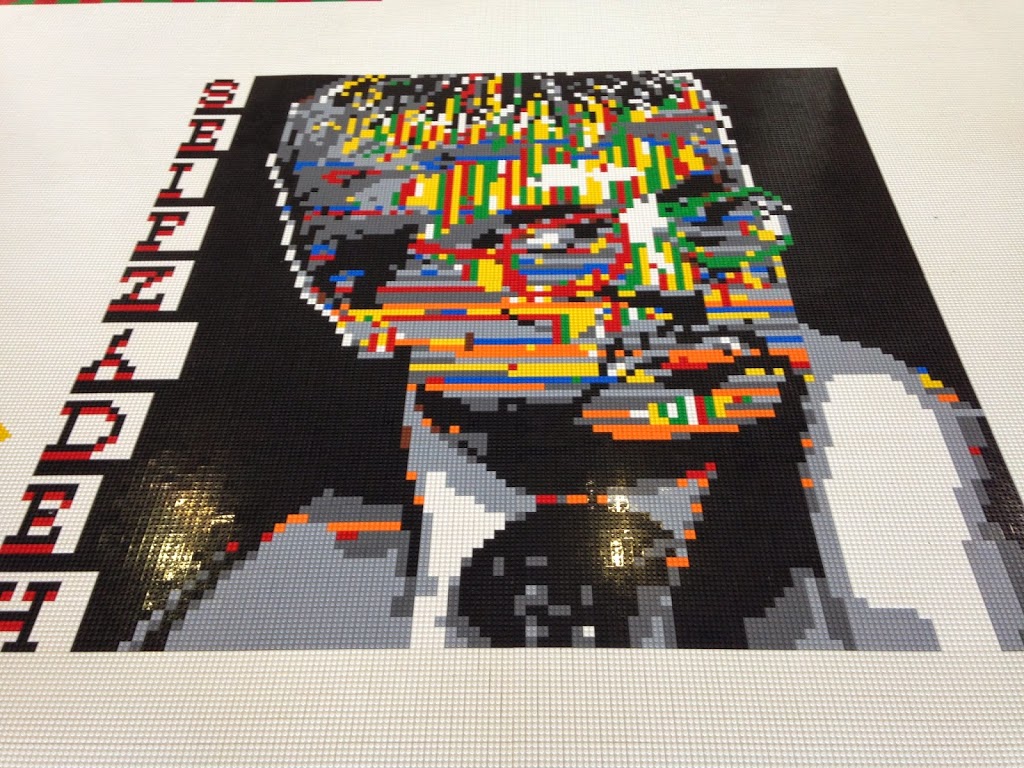

In the next room, Trace portrays over 170 faces of political prisoners and exiles using plastic LEGO bricks. Foregrounding something as serious as the injustice of governments (democratic as well totalitarian) acting against their own citizens in the medium of children’s toys seems like an odd juxtaposition. Each pop portrait looks like a pixilated heat scan, not far from abstraction—perhaps inspired a little by Warhol silk screens or distant cameras? What remains is just a bright trace of the individual. At first, it’s tempting to look for the more famous names, the late Nelson Mandela, Aung San Suu Kyi, Chelsea Manning, and of course, Edward Snowden. But like the LEGOs themselves, these are points of access. And then I was overwhelmed by the enormity of all these human beings suffering for advocating freedom and justice. Thankfully, the @Large website has biographies of each person so their memories are not left on the factory floor.

|

|

Refraction, 2014

photo: Jan Stürmann

|

Interestingly, the most physically beautiful and complex piece in the installation, Refraction, can only be seen from a distance in the lower gun gallery. After being immersed in viewing the kite and walking around (although not on) the LEGO tiles, seeing this sculpture—wings made of metal panels from Tibetan solar cookers—serves as a reminder that art, like freedom itself, is not guaranteed. You can barely experience the most beautiful form in the island, a wing too heavy for flight. Freedom is never certain.

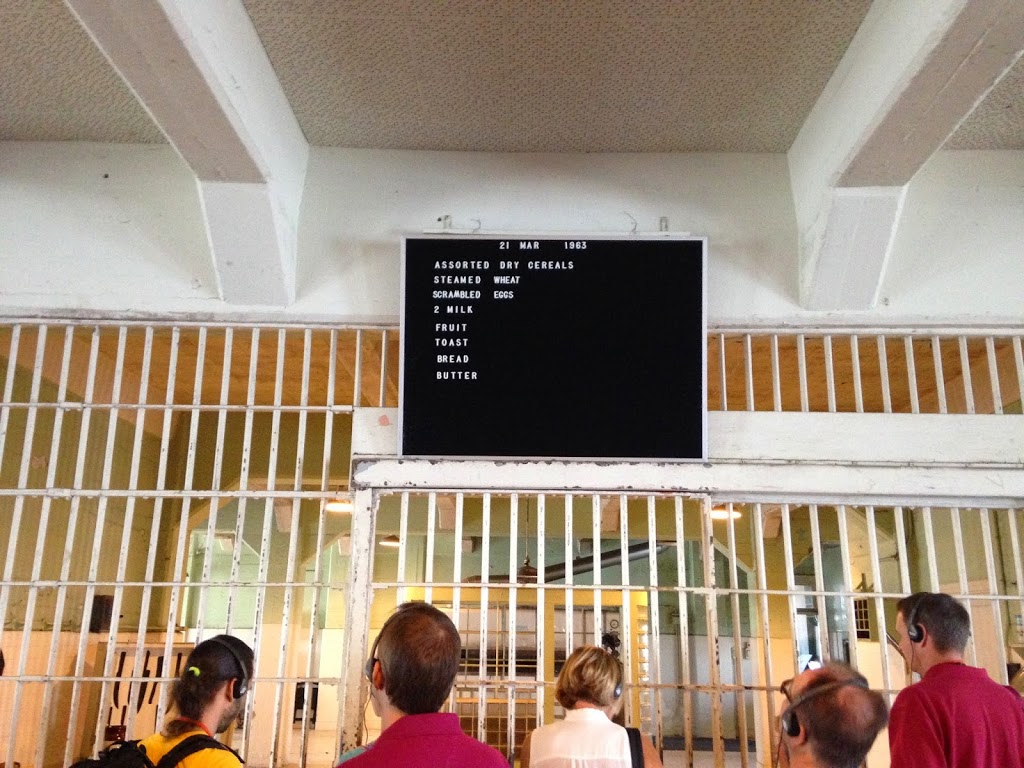

After the claustrophobia of the gun galleries, being outside with vistas of the bay—which prisoners rarely saw—is restorative. A further walk leads up to the door of the main cellblock, where you enter as prisoners did and are faced immediately with the same series of completely open showers that they saw. The associations with the final solution, though not intentional, are obvious.

|

| Blossom, 2014 photo: Jan Stürmann |

|

| photo: Kenneth Caldwell |

|

| photo: Kenneth Caldwell |

Up the stairs are the hospital and psychiatric observation rooms, which are usually closed to the public. In the sinks, tubs, and toilets of the hospital, the artist has inserted precisely measured groups of porcelain flowers. At a distance, they appear to be bunched-up paper, some kind of waste. On closer inspection, they reminded me of kitschy trinkets that tourists might find in Chinatown a few miles away. Weiwei entitled these groupings Blossom. The longer you look at them, the more they turn into groups of pure white blossoms, white like the porcelain containers they rest in. They are monochromatic, a commentary perhaps on a colorless life behind bars. Yet they are also a contrast to that life because they are so delicate, so fragile within the stolid vitrines of fluid waste inside an oppressive monolith. One color, many layers.

|

| Ilumination, 2014 photos: Kenneth Caldwell |

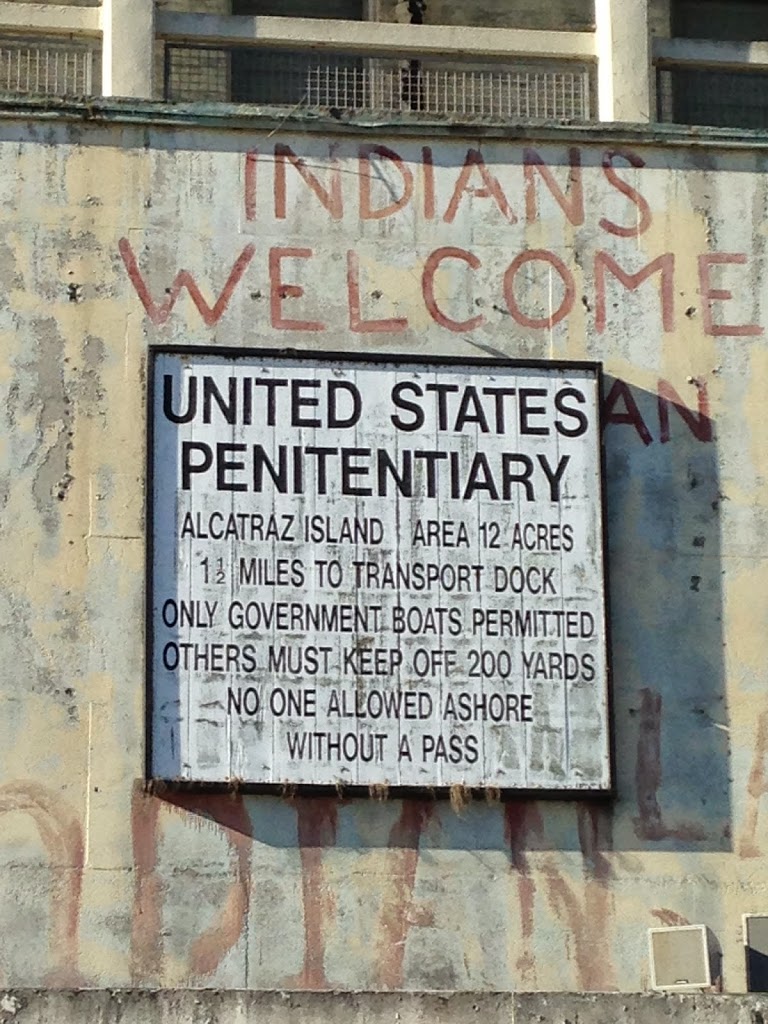

Nearby, in the psychiatric observation rooms, I felt another sudden urge to get out as fast as possible. But I was drawn in by an almost hypnotic chanting of Tibetan monks and Hopi Indians. This piece, entitled Illumination, reinforces the well-known link from Chinese dissidents to Tibet. But few people are aware that Hopis were imprisoned on Alcatraz in the 19th century when they wouldn’t let their children attend U.S. government schools. I was also reminded of the Native American occupation of the island for nearly two years in the late 1960s/early 1970s.

|

| Stay Tuned, 2014 photos: Kenneth Caldwell |

Back downstairs and over to A Block, which was not renovated when the military prison became a federal penitentiary. The cells were later used by prisoners for typing up their correspondence and for storage. Here, the artist has turned each cell on the ground level into a space commemorating a well-known political prisoner. Stay Tuned encourages the visitor to sit on a simple stool in the small cell and listen to some kind of text or song created by prisoners such as Russia’s Pussy Riot, Chilean poet and musician Victor Jara, Tibetan singer Lolo, and of course, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Their voices reach across oceans, years, and concrete walls. With so little “art,” this installation finally causes you to just sit and feel the tiny enclosure that is a prison cell.

|

|

Yours Truly, 2014

photo: Jan Stürmann

|

|

| photo: Kenneth Caldwell |

Exhausted from the walking and contemplating, you end up in the former cafeteria wondering, what can one person do in the face of all this oppression? Instead of predictable organic snacks on beautifully made, locally sourced wood tables that you might expect in the Bay Area, there are pens for you to write a note on a pre-addressed postcard with images of the countries where today’s political prisoners are being held. Yours Truly is a tidy conclusion to the show, but it does serve to remind us that one person can make a difference and help free people. Each of our voices helped Ai Weiwei get released from prison so he could, with help from hundreds of people, make these pieces of art. We hope that one day he and the other prisoners will be able to physically stand with us. As Edward Snowden has shown us, preserving freedom takes a lot of thinking and a lot of action. But one person can make a difference.

More information:

http://www.for-site.org/project/ai-weiwei-alcatraz/

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/21/arts/design/ai-weiwei-takes-his-work-to-a-prison.html?_r=0