It takes guts to write a biography of Joan Didion, one of the country’s most highly regarded writers, while she is still living. It takes even more guts when she and her friends won’t cooperate. If she won’t help, you are going to end up relying on the unreliable: an old lover who considered suing Didion because he thought she was portraying him unfavorably in her fiction (talk about a fool’s errand), or an artist who speculated that Didion’s husband was gay (brother-in-law, yes-husband, not so much), or her late daughter’s husband’s son. If you try to replicate Didion’s precise and elliptical style, you’ll fail. She’s the best. And no one can quite match up.

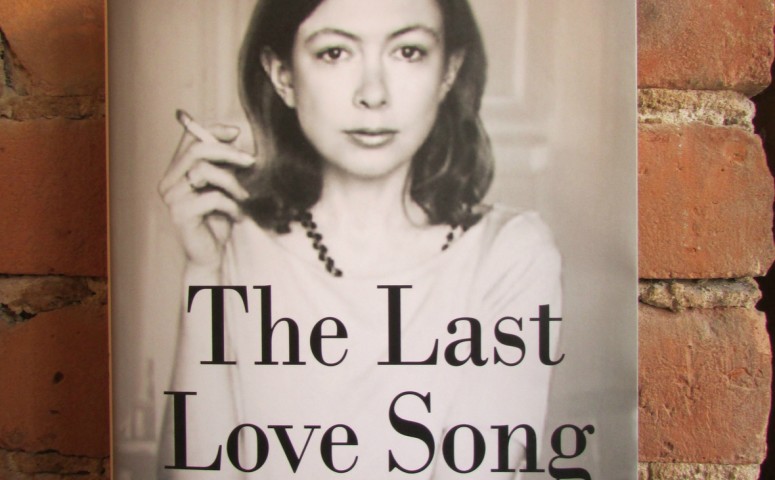

Tracy Daugherty, the author of The Last Love Song: A Biography of Joan Didion, has to rely on these sources, with the result that he speculates a great deal about his subject’s youth, husband, and daughter. He gets geographic facts mixed up, and I suspect that’s not all. He is probably best when he tries to do what Didion does: read the texts carefully. But that isn’t enough. You still have to write in your own voice.

Daugherty uncovers some wonderful tid bits. The essay that won Didion the Vogue prize was about the regional architect William Wurster. Wurster emerged from California’s vast agricultural plains with a spare style and moved in elitist circles even as his politics moved leftward. Not unlike Didion herself.

What Daugherty is most successful at is portraying the incredible ambition that fueled this apparently frail, shy, waif-like person. After all, she had the audacity to reach beyond her Sacramento semi-aristocratic bubble to land the very prize Jacqueline Bouvier had won a few years earlier. After Didion won the prize for her Wurster essay, she found the leader of the pack of the 1960s New York literati, Noel Parmentel. He introduced her to whoever mattered in New York, including her future husband, John Gregory Dunne—a near aristocrat, Hartford Catholic division—and his even more ambitious (not to mention conflicted) producer brother, Nick. And Hollywood’s doors breezed open.

What isn’t so obvious is the Dunne’s fraternal competition. Daugherty mentions it in passing, but it must have been central to the family dynamic. Nick was happy to help as long as he was the head producer, the one at the top of the pyramid. When he burned out on booze and drugs, the Didion/Dunnes were still in triumphant mode, with generous incomes from films, articles, and books. After the required time licking his wounds, unstable climber Nick Dunne reemerged as sober Dominic Dunne, writing about his daughter’s horrible murder and receiving his own glamorous pedestal at Vanity Fair courtesy of Tina Brown.

While he was not exactly a literary lion, Nick/Dominic’s gossipy accounts of the underside of the glitterati and his roman à clefs outsold the books by his more highly regarded brother and sister-in-law. Check. But of course, he kept his own homosexuality hidden for the rest of his life. Checkmate. Although Daugherty mentions all of this, it is not really central to the narrative. Indeed, it is hard to find the yellow stripe down the middle of the foggy highway, although an account of Didion being unable to find the stripe in the Malibu fog feels significant. She often writes of being confused, frightened, of taking a wrong turn. As if she were driving in a fog. But then the veil parts and she finds her way, clear and sharp.

One problem with trying to write like Didion is that one of her main tools is the ellipsis: what is left out. The effect is the same one produced by all that white space in modernist graphic design. When trying to write an in-depth biography, however, it’s challenging to be elliptical. The result is that the rhythm is off throughout the book. Nobody can do Didion like Didion. It’s hard to end a paragraph with an ironic sentence and then fill up the next several paragraphs with biographical odds and ends and juicy gossip.

Not that there aren’t some very funny lines. My favorite: “And who was Patty Hearst? Joan Didion with a carbine.” A pioneer sister, Daugherty suggests.

Although Daugherty covers the Manson murders and Didion’s attempt to write a book about Manson follower Linda Kasabian, I was surprised he didn’t spend more time on it. It is a perfect moment of destabilization for the Didion/Dunnes.

Daugherty is at his best when he is reading and explaining the text, whether it is the published works or the unpublished material in the Bancroft Library (an institution Didion has also relied on over the years.) But a critical overview of her writing spiced up with a few questionable sources isn’t quite a biography. I think it is going to take somebody else to read the texts over again with a surer voice and access to Didion herself to really get at the woman behind those oversized Celine sunglasses. Good luck with that.