Baltimore may epitomize America’s arc. Flying high during the booming industrial age and trying to reinvent itself forever afterwards—all at a great human cost. Visiting Baltimore in the middle of winter means that you won’t see throngs of scantily dressed tourists flocking to the Inner Harbor. In fact, you will see very few people at all, but the most hearty of homeless folks begging on the motorway. It is a city with great beauty and great decay. It’s not as bad off as Detroit, but it isn’t rich like nearby Washington. If you don’t want to stay in a corporate hotel, we loved Rachael’s Dowry Bed & Breakfast. A beautiful glimpse into a privileged past.

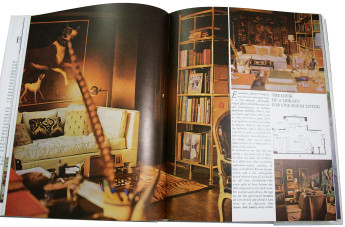

When we returned home to Oakland, I looked for quotes from famous Baltimoreans whose work I know. Two came to mind. Both are gay men rooted in the 20th century. First is Billy Baldwin, arguably America’s most important decorator of the middle of the 20th century. Born in 1903, he brought informality, color, and humor to America’s well-heeled tastemakers, including Jacqueline Onassis, Cole Porter, and Diana Vreeland. I have written elsewhere about a house he designed in Mallorca that I saw a photo of as a young boy. That image on the cover of a shelter magazine left me asking questions about what is real. What is inside? What is outside? What is true?

Many years later, the photographer Francesco Scavullo asked Baldwin about Baltimore. Here are a few telling excerpts from the interview.

…I grew up in Baltimore, which was a very conventional city in one sense, but also almost amoral. It was the most exciting place socially, in the twenties and thirties, and everybody wanted to come there because they had a very good time.

Did you drive yourself a lot, push your career?

I did after I left Baltimore, which was the city of absolute pleasure. Baltimore was to die, simply wonderful. But I awakened one day at the age of thirty-three and I thought, “This has got to stop. I’ve got to get out of here, or I’ll become a fat pig full of mint juleps. And I’ll be miserable.”

And then there is John Waters, who stayed. His movies are so outrageous that you have to laugh, or throw up. His recent writings have entertained me more than his films. He looks like a character out of the first talkies, with his pencil-thin moustache, but instead of wearing a Brooks Brothers suit, he sports a Commes des Garçons jacket that is intentionally a perfect mess. Like Baltimore itself, I guess—a whisper of the past with its seams torn asunder.

Here is an excerpt from a recent interview in The Daily Beast:

“I was around for the first Baltimore riots,” Waters says. “My first apartment in Baltimore was on 25th Street and Calvert, and there were tanks outside of my house. Everywhere was burning. Believe me, these riots were not as bad as those. But the riots in Baltimore this time were more widespread than what you saw on CNN, because if you watched CNN, you’d think it was that one big fire and Penn and North. The Penn-North neighborhood, I guarantee you, 80 percent of white people I know haven’t been there. I used to live [around] there. I used to live in an all-black neighborhood…The problem in Baltimore is that…there is also an equal number of poor white people. I really wish that they would team up. The poor people of Baltimore need to make it a class issue, not a race issue.”

I just found out that Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, was born in Baltimore and grew up there. I wonder if John Waters has done anything with that.

For architecture buffs, there are grand buildings and monuments as well as industrial buildings that have been saved or just left to decay. By the 1950s, the industrial production that had made both Baltimore and the country prosperous was on the wane. The riots in 1968 following Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination marked another turning point in the city’s demise. Many neighborhoods never recovered. The city has seen enormous government investment as it tried to become a tourist and convention destination. Although well-intentioned, most of the modern buildings are banal.

On our first morning, we visited one of the most photographed buildings of the Inner Harbor, Ben Thompson’s Harborplace, a festival marketplace developed by the Rouse Company and opened in 1980. There has been no full-scale monograph on Thompson yet, but he is remembered for the Design Research retail chain that he founded in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the handsome concrete and glass building that housed it. He wasn’t afraid of color, bold signage, or retail itself.

Although trained at The Architects Collaborative, Thompson could bend the rules of modernism to create a sense of place. His concrete buildings at the intersection of Pratt and Light streets evoked the industrial buildings of Baltimore’s old port but were also resolutely modern. Over time, the pressure of keeping space rented has eroded the original architectural concept, and in the case of Ripley’s Believe It or Not museum, completely obliterated it. There is talk of revitalizing the revitalization.

In its quest to attract tourists, the city created a free shuttle bus called the Charm City Circulator, which covers the center of the city on three routes. We jumped on the bus because it was just too cold to walk. As soon as I sat down, a homeless man reached out to touch me. We rode the two routes for a few hours. At one point, we got off to check out the legendary Owl Bar in the former Belvedere Hotel. That was a mistake. The ten-minute wait for the next bus was excruciating. Interestingly, most of the riders seemed to be locals, who were happy to have warm and free transport. It’s probably used more broadly in the spring and summer. It is a way to get around inexpensively, but I wouldn’t call it charmed.

At first blush, Baltimore doesn’t seem like a foodie town. But friends told us they liked the Thames Street Oyster House. The crab cakes are a favorite in Baltimore. They are made mostly out of crab, and don’t look anything like the bready things we get in California. And we had good ones in a few places. Because of our requirements for a late hour, we ended up having dinner in an overpriced steak house called Supano’s. The décor was modest, the waitress talked too much, and the karaoke started at ten. But the food turned out to be delicious. Really chunky crab cakes, a serious steak, and old-fashioned homemade pasta.

If you need a late night pub with edible food, try Pickles Pub. It’s not gourmet, but on a cold winter night, a bit of chili and fried pickles(!) hit the spot.

The highlight, though, was a restaurant called Woodberry Kitchen. It’s a ways out of the city center, so we got a Zipcar rather than paying the usurious Uber rates (the result of too few drivers willing to accept the low wage and the freezing temperatures). It was one of the early farm-to-table restaurants, and somebody cares very much about the quality. Every course was beautifully prepared. And I’ve never had oatmeal ice cream before!

You might want to know why we chose Baltimore as a destination in the middle of winter. Paul’s opera, The Ghost Train, was having its premiere by the Peabody Institute at the B&O Railroad Museum. The director of the program, JoAnn Kulesza, and director Garnett Bruce did an amazing job of staging the opera inside a cavernous landmark. The cast sang beautifully as they moved in and out of the railroad cars. When the ghost train approaches, the lights of the engine turned on, and steam came out of the smokestack! We were humbled by the presence of so many good friends and supporters from near and far who braved a Baltimore winter. A weekend we won’t forget. And if you are in Baltimore, be sure to visit the B&O Railroad museum. Great for families—kids love trains!

The other architectural monument that we explored was John Russell Pope’s Baltimore Museum of Art. The institution is most famous for the Cone Collection of Matisse and other modern painters. The Cone sisters were friends of Gertrude Stein and built close friendships with her friends Matisse and Picasso. For art enthusiasts, these paintings alone are worth the trip to Baltimore. The museum also has strong collections in African, Asian, and American art. Should you go to the museum’s restaurant (named Gertrude’s!), it is probably wise to make a reservation.

On the modern art front, we took an hour’s drive to Potomac to see Glenstone, the private art gallery of the billionaire Mitchell Rales and his wife, Emily. The area was rural until a few decades ago, when it became subdivided for McMansions in the Federal style. Rales bought up over 200 acres and took out the beginnings of a subdivision. With Peter Walker’s help, he returned the landscape to something quite stunning. He hired Gwathmey Siegel to design him a modernist mansion and, across the pond, a companion art gallery.

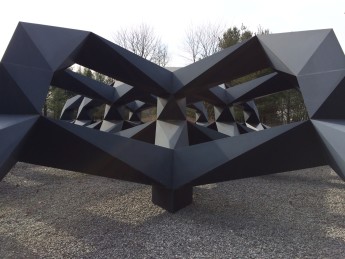

The visit is free, although it does require a reservation. Don’t arrive more than 15 minutes early—they won’t let you in. Behind the gate is a curving drive past a hideous Jeff Koons (is that redundant?) followed by a Serra emerging from the rolling earth and then a monstrous Tony Smith.

Visiting here is like going to a true white-glove doorman building in New York. Someone to guide you every step of the way, except that they are dressed like graduate art students. First there is the man at the gate who smiles but is firm. He tells you that someone will greet you at the bridge to tell you where to park. More smiles. Park right here if you don’t mind. And if you are interested in a short walking tour of the grounds, another woman explains the history of the place and the sculptures, including a stunning Ellsworth Kelly sculpture on the other side of the pond.

Once you’re inside, someone takes your coat, and the ratio of visible staff to visitors is 1:1. The folks who accompany you around the gallery are not guards, but rather informed guides. They are very friendly and admit it if they don’t know the answer. They are perhaps a bit too eager to engage, asking you, “What do you feel about this piece?” That’s for my therapist, thank you very much. But it’s clear that the Raleses want an intimate art experience.

When we went inside, I was at first disappointed to find out that the artist on exhibit was Fred Sandback. I know his work from DIA: Beacon, where there is a permanent display. After spending an hour with his works, I realized that at DIA, the heavier works of artists like Richard Serra, Michael Heizer, and Donald Judd overpower him. His work is ephemeral, mostly strings of acrylic yarn that delineate and question the experience of space. After the exhibition comes down, the material is discarded. As a collector, what you acquire are a set of instructions. What is art? Who owns it? What is space? What is true?

As it turns out, the Rales are constructing a large addition by Thomas Phifer. It will feel like several buildings buried in the hillside. Look for it in 2017. We’ll meet you there.

Further readings

https://www.baltimorebrew.com/2015/10/02/a-more-local-less-mall-like-harborplace/

http://www.theguardian.com/travel/2014/nov/28/john-waters-baltimore-us-way-i-see-it

Travel Tips

Rachael’s Dowry Bed and Breakfast