Modern architecture has its roots in social change. On the 50th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement, which was an important catalyst for social change on campuses in the 1960s, it is worth documenting the intersection of design and radicalism that followed. This fall, an exhibit entitled “Design Radicals: Creativity and Protest at Wurster Hall” will be on view in the Wurster Hall library at the University of California, Berkeley. The show is curated by associate professor of architecture Greg Castillo and exhibition designer Kent Wilson. What follows is a two-part interview with Greg Castillo.

Interviewer: “Design Radicals” is both an exhibition and a series of events?

Greg Castillo: The show opens on October 16 with a talk by the scholar of political poster art and archival activist Lincoln Cushing, who maintains the Docs Populi website of graphic arts dedicated to social justice. While most of us know the outlines of the story of the Free Speech Movement, we are not so clear on the impact that it had on visual arts and design. Was there any crossover? How could that have informed people’s work in design? I started to investigate that. This is a first pass at some of those findings.

Interviewer: What’s in the show?

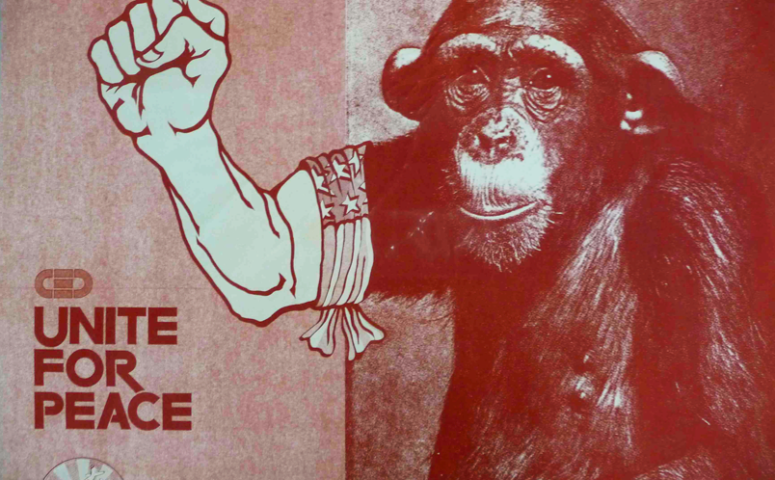

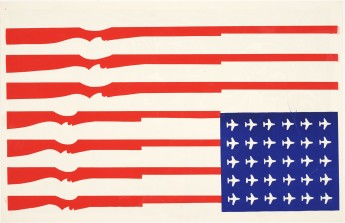

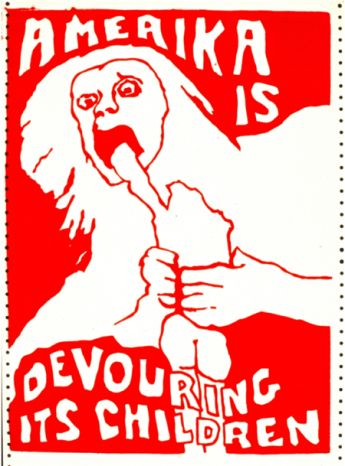

Castillo: A large part of the show is dedicated to posters that were made in Wurster Hall in 1970. At that time, Nixon’s Cambodian incursion, the Kent State shootings, and the shootings at Jackson State in Mississippi had started a campus conflagration felt across the United States. Administrators at U.C. Berkeley, and also within Wurster Hall, decided that they would allow students to use their time productively to create antiwar committees, to mobilize Berkeley neighborhoods in terms of antiwar activities, and to essentially turn the first floor of Wurster into something very much like a propaganda factory. Instead of Andy Warhol’s pop factory, this was Wurster Hall’s political poster factory.

CED posters of May 1970

Anonymous

poster by Jay Belloli

Interviewer: What did they do?

Castillo: During that period, it’s estimated that 50,000 posters were printed. Students sold the posters for a penny apiece. Or you could pay more to have a silkscreen image put on the back of a shirt, but you had to bring your own garment. And we know that on a good day, they were able to raise about $500, which adjusted for inflation would about $3,000 today. This was a broad-based, popular “graphic arts insurgency.”

Interviewer: It’s not typical for student movements to keep such diligent books. Where did you find this information?

Castillo: The reason we know so much about the finances was that these activities, and especially the fact that the campus administrators sanctioned them, outraged Ronald Reagan, who was then California’s governor. Acting through the University of California Regents, he hired an accounting firm from San Francisco called Haskins & Sells—it’s still in existence under a different name. They did a very careful audit to see whether materials and equipment that were supplied by the State of California expressly for the purpose of educational use were being used to make protest materials. I think it’s pretty clear that, had the accounting firm found evidence of misuse or misappropriation of that material, there would have been a purge of student activists, and probably more to the point, a purge of faculty and administrative staff who had been their accomplices.

We know from looking at the documents produced by Haskins & Sells that, in fact, there weren’t any grounds for the assertion of misuse of state funds. From their report, we found out that almost all of the paper for the posters came from the refuse bins in back of the campus computer center. This was an early example of recycling and radical repurposing of materials. Along with the Wurster Hall protest posters loaned by Lincoln Cushing, the Haskins & Sells report is on display in the exhibit.

Interviewer: What else does the project cover?

Castillo: The other part of the exhibition tracks the work of a pivotal figure in countercultural design pedagogy, at least here at U.C. Berkeley, and that’s Sim Van der Ryn. Before being appointed California’s first state architect under Jerry Brown, Sim sponsored a series of experimental studio courses. His collaborators called him “Scout” because he would chart a path, find a new thing, ride that wave, and pull people behind him. While his colleagues were doing the project, Sim would be off looking for the next big idea.

Interviewer: Where does this story begin?

Castillo: The first big idea was an intervention in elementary school education here in Berkeley by a cohort of young professors and lecturers, some with young children. Sim’s main compatriot in this project was a young lecturer named Jim Campe, whose wife was an elementary school teacher. Together, they looked at what was happening in elementary school teaching and thought—now this is my interpretation—“We’ve made all of these breakthroughs; we’ve walked away from some of the stultifying aspects of mainstream culture. And then we’re going to put our children into schools, that inculcate mainstream thinking? How can we find an alternative that will yield a liberating pedagogy for children?” They found the conventional setup of children in ranks at desks facing a blackboard absolutely antiquated. Their alternative was to have children build things. They believed in craft and the notion that doing and making with your hands, doing things as collaborative activities, would develop important skills in children— manual, intellectual, and social skills.

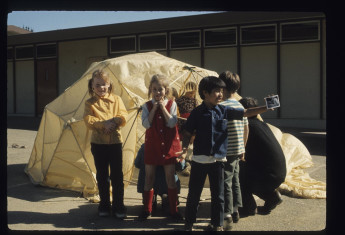

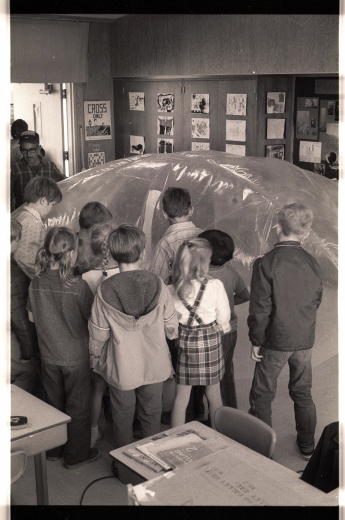

They had children assemble geodesic domes and cover them with army surplus parachutes to play and hide in. They built inflatable structures in classrooms and had kids running in and out of them, very much like an Ant Farm dream. They had kids build their own “carrels,” little two-story nooks where children could claim their own place in the classroom to cool out. They were creating an informal urbanism within the classroom with these favela-like self-built structures.

Interviewer: What followed that? There must be a bus involved! Geodesic domes and buses!

Castillo: Jim Campe spearheaded an initiative to buy an old U.S. mail services surplus van and rehabilitate it. They painted it up, called it the Eagle, and went around doing mobile interventions at local schools. They would have all of the stuff they needed, much of it acquired for free from castoff materials. Their motto was “Trash can do it.” So they were very conscious of the notion that they were taking what a rich consumer society threw away as trash, reusing it with very low environmental impact. They were very early environmentalists—using it creatively to teach students how to do things.

Odyssey School Experiment

Campe inflatable design

photos courtesy: Jim Campe

Interviewer: Was there an anticapitalist thread here?

Castillo: One often thinks of the counterculture as being against capitalism and commodity exchange. But that’s actually the opposite of what happened. So, for example, for this school initiative, the Odyssey School Initiative, they put together something that they called the Farallones Scrapbook. It was a document of their classroom modifications and a do-it-yourself guide to primary school reform. The Farallones Scrapbook was initially printed up in a small number and sold as more or less an underground publication. It was part of a general trend in local counterculture reexamining child education. There was also a journal called Big Rock Candy Mountain, which was modeled on the Whole Earth Catalog and published here in Berkeley; it also looked at ways of teaching children that were not so stultifying.

The Farallones Scrapbook sold out very quickly and was picked up by Random House as a West Coast lifestyle publication and sold tens of thousands of copies. That turned into a successful commercial venture. This Bay Area circle of counterculture folks were like venture capitalists, taking that money and putting it into the next initiative.

Interviewer: Tell me about Sim’s teaching initiatives.

Castillo: Sim and Campe created an architectural studio course called “Making a Place in the Country,” also known as the “Outlaw Builders Studio.” Sim was one of the very first people, as an architecture instructor, to reject the traditional preponderance of male architecture students. One of the guidelines for selection was achieving a 50-50 mix of women and men: something that was not easy to do in 1972. The students who were selected would have to agree to leave campus for three full days every week. They would go up to a remote forested area in Inverness, in Marin County. First they would learn how to forage for food in the forest and dig up mussels at Point Reyes, for example. They would then proceed to plan and build their own communal settlement, with sleeping shelters, a drafting studio, a mess hall, an outdoor oven, composting toilets, and a chicken coop.

Interviewer: Was this a utopian escape?

Castillo: At this moment in time for the counterculture, people were trying to figure out whether they should stay in cities or move back onto the land. You have to remember that this was after the confrontation at People’s Park, when Alameda County Sheriff’s deputies fired shotguns at protesters, sending dozens to the hospital and killing a bystander; this was after the National Guard sprayed tear gas indiscriminately over the campus using the same kind of helicopters deployed in Vietnam. Sim’s studio was geared to provide students with a set of skills that they would need if they decided to go out in the country and start new communities. Construction materials included old virgin redwood chicken coops from Petaluma that were being removed.

Interviewer: What about the criticism that these kids were just building Sim Van der Ryn’s country house?

Castillo: I think that came mostly from other faculty members. In fact, Sim has a house there, but they didn’t build it. They built what are today a collection of outbuildings. Some of them have had to be pulled down because they were not built according to any code: that was one of the notions of the “Outlaw Builder.” This studio was an exercise in teaching building and social skills. People were put in a difficult situation, having to just eke it out on a plot of land, and had to learn how to live together as a community. That was an important point. Students had to keep journals for this course, and one of the students said that she was learning to build both a place on the land and a home for her spirit. There were a lot of levels of meaning to what was going on.

Interviewer: And was there a monograph?

Castillo: Like the previous project, this project yielded a report that was called Outlaw Builder News, sold on Telegraph Avenue as a $0.75 underground journal. They were able to sell as many as they could print. And that provided money for a final project that we look at in this exhibition: an experimental structure called the Energy Pavilion that came out of a studio called Natural Energy Systems.

Interviewer: What year is this?

Castillo: 1972-1973. The students were trying to understand and put into practice ecological and solar architecture. Incredibly enough, from our perspective now, there were so few articles and journals on that topic that the first quarter of the course was dedicated to simply finding enough materials to put together a course reader. Again, there was a financial payoff. The course reader was picked up by Random House, titled Natural Energy Systems, and became one of the very first mainstream handbooks on solar architecture.

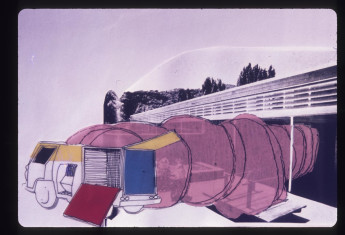

Students started by trying to formulate an alternative to what they called a “techno-fantasy house,” an alternative to a house that sucked up water and external energy sources and generated wastes that just disappeared down sewage lines, never to be thought about again. They were trying to figure out the internal infrastructure for an autonomous house. And they built that autonomous house service core as another outlaw building in front of Wurster Hall in the spring of 1973. That structure was called the Energy Pavilion. Students manufactured very early solar panels, hot water solar panels, right here in the Wurster Hall shop. They manufactured parabolic solar reflectors and rainwater collection devices; they had a little wind-driven generator that generated electricity. When the wind wasn’t blowing, they had a bicycle device which would either power a generator or, believe it or not, a grain-grinding mill.

Interviewer: Like on Gilligan’s Island?

Castillo: Exactly. They created a closed-loop system for food production with beds of snow peas and lettuce which, according to their proposal, would be fertilized by a composting toilet. I’m told by Sim that this thing was picked up as a curiosity by a local television station, and within days they had lines of people wanting to visit it. It also attracted unwanted attention from the Campus Aesthetics Committee, which did not like the idea of “outlaw building,” especially on campus. So they told Sim, “Okay, great, you’ve done it. That thing has to be torn down before commencement exercises. We don’t want to expose these poor students’ parents, who are coming from all over, to this bizarre-looking object with a composting toilet in front of one of the buildings.” Sim was disconsolate, but the Energy Pavilion came down.

Interviewer: He was incredibly prescient.

Castillo: The interesting thing is that that it happened in June 1973. That October, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries decided to punish the West’s support for wars in Israel by creating an artificial spike in oil prices. The result was the world’s first energy crisis, the incredible spectacle of cars waiting hours in line trying to get gasoline, the speed limit going down to 55 miles an hour to conserve energy. These are conditions of a world that Sim and his students were predicting, or showing a solution for. That world came into being just a few months after they built their weird-looking experiment in natural energy systems. But by then the Energy Pavilion was gone.

I should mention that the Energy Pavilion was also built primarily out of recycled materials, in this case a redwood barn in Hayward that was too close to train tracks and which Union Pacific Railroad wanted removed. Again, Sim volunteered students to demolish it for parts. Can you imagine university lawyers allowing the students to do any of that stuff today?

The Energy Pavillion

courtesy: Sim Van der Ryn