Artist Lonnie Holley works in a variety of forms and materials. His first pieces were sandstone carvings, tombstones for two of his sister’s young children, who had died in a fire. His materials were discarded pieces of sandstone from the foundries of Birmingham, Alabama. He went on to create sculptures from found materials he collected wherever he went. In his 60s, he started recording music and has released several albums.

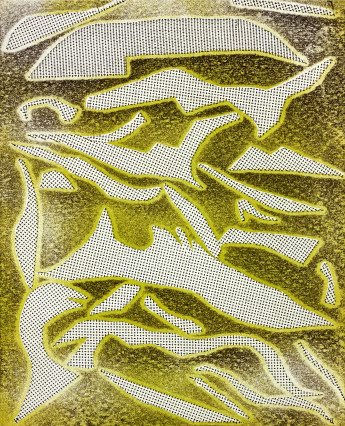

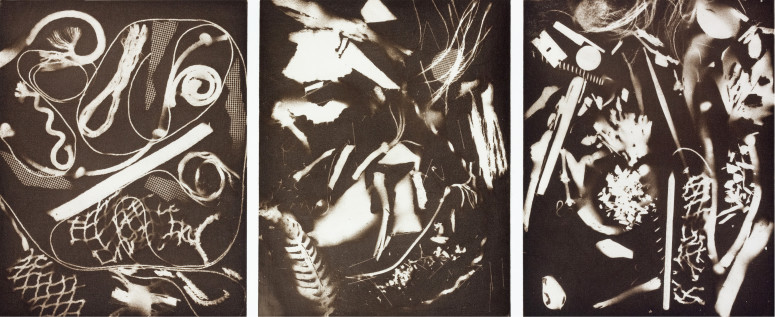

Over the years, he has also done a kind of DIY mono printing, pressing found objects onto painted paper. Last year, Paulson Bott Press invited Lonnie Holley to come to the studio and collaborate on printmaking, and I had a chance to speak with him.

Q: What has it been like working with Paulson Bott Press?

Lonnie Holley: You know, they have been incredible. Their hospitality is big. Once I get the pieces laid out on the plate, they would show me what will work and what won’t. So I’m just appreciative for the hospitality of all of them, everybody—all of the staff I’ve been introduced to. And they’re making me feel real, real welcome.

Q: When you first started making art, how was it received in your community?

LH: When you did art in the community, it was like you had went berserk or you had gone crazy…

Q: Because no one else did it?

LH: It was something that you did not do, because everybody—you had peoples that had different kinds of religion and stuff. They would come by and say that you were making idols, and you were doing something against the will of God. And you was just an outcast. So, I mean, it was a long time before people even allowed or accepted what I had to say in church about the material that I worked with. And that’s where—I did this song called “The Other Side of the Pulpit.” Because I had learned so much and was learning so much. It was like I was an outcast in society.

Q: Your sandstone sculptures became known after a fire burned down your house. What happened next?

LH: Everybody in the city started bringing stuff to my mama’s house. They were dropping off bags and bags of clothes for everybody. We had got burned out. They would come running up the steps to Grandpapa house, going up the steps giving Mama envelopes of money. And I felt so proud of Mama. It was just so much all of a sudden. And it was all about that art. And I didn’t know what art was.

Q: So how did you move from the stone carving to this other work?

LH: I always was doing something. Everybody said that I had been possessed by my grandfather’s spirit. And I didn’t know what possessed mean. I always thought of it as an ugly something. I always thought of it as like I’m more of an unfit thing, because I got Grandpap’s spirit.

Grandpap worked all the time. Grandpap dug iron ore. Then he would leave the job, and he would take the oxen away. And he had his own ox and his wagon. So if you had your own ox and wagon, it was like you had your own truck. And they sent you to the mine. And you load out. And you bring this stuff across the state. You was working a normal day of work, would go to the mine. You use whatever you had at the mine.

Q: What do you see as your purpose as an artist?

LH: My thing as an artist—that’s trying to give people that are living a sense of you’re not to die yet, because I have not gotten your information. I haven’t gotten your life story. You was uneducated. You was considered to be illiterate. You couldn’t read, or you couldn’t write. But everybody have a concept of speaking. Speak to me.

When Jesus went to the tomb of Lazarus, Lazarus was considered to be dead. They had dressed Lazarus. They had put all this stuff on Lazarus. Lazarus was in a state of concentration. Okay. I got to die, so I’m accepting death is going to come. And go ahead and anoint me. And all the time that Lazarus got to hear anything was when these women came in. His mother, his auntie, and somebody else came in—you understand?—to speak to him. Lazarus, you now have leprosy. Nobody don’t want to touch you. Your soul is so nasty. Your body is so filthy, nobody want to have nothing to do with you. You stink. So Lazarus gets this idea that nobody want to have anything to do with him. And then he said, “Shut the door. Roll the stone. I don’t care.”

You forsake yourself in the process of death. By not having nobody to talk to, you start talking to yourself. And when you feel that self is not listening to you no more, then you’re ready to die. The average man, the average anybody that has any information—once they—this source of information has ran out, they either go back to get some more, or they say, “My time is up.”

Q: Can you talk about the connection to your music?

LH: Music has always been a part of my life. I’m like my grandmama and my granddad. As far as my grandmama Momo was concerned, the reason why we called her Momo—because she walked around and moaned and groaned all day. Where we don’t see that as a way of musicians. We didn’t see moaning and groaning—is I didn’t tell you, Oh, Lord. I didn’t cry it out. I moaned it out. So I kept constantly this inside. But I was content with the amount that I let out. Because I know I’m walking in the midst of the baby. And I don’t want to make the baby want to get up. So because the women that was in the process of growing their children—they would walk with a soft moan and still exercise the same musical privilege that was supposed to be outlet for our brain.

Our brain need an outlet. Otherwise we crowd it. And then Grandpap used to call you bonehead. He said, “You bonehead.” Because everything—you want to keep it under your dome. You want to keep it in your bone. You want to keep it under your head. See, I let it out. So the birds heard me. And they would echo my sound. You see?

All images courtesy Paulson Bott Press