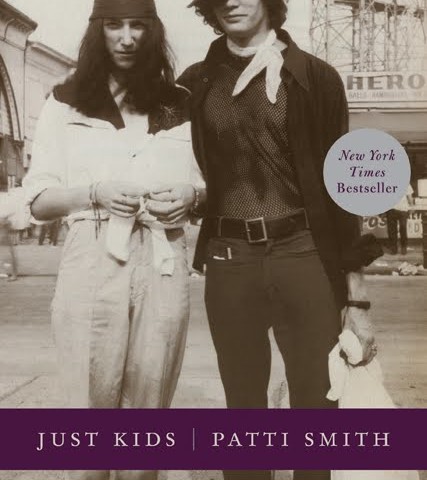

Patti Smith’s memoir Just Kids is a love story that could take place only in New York in the 1970s. A love story about a woman that links poetry, prayer, God, and love in surprising ways. A love story about a man fighting to get out from under a Catholic childhood.

Smith’s plain language captures the time when she and her young lover and soul mate Robert Mapplethorpe were not yet famous. Except for a few pages about his last days, the memoir mostly covers the period before she made records, before he got a good camera from Sam Wagstaff . Walking down Eighth Street in 1978, Mapplethorpe says, “Patti, you got famous before me.” There are several lessons in this memoir. If you want to be famous, be sure you pick a good lobby to hang out in. Back then it was the Chelsea Hotel’s.

Patti Smith

ROBERT CHELSEA HOTEL 1970, 2009

Platinum print, ed. 1/3

10 x 8 inches, 25.4 x 20.3 cm (SMIH-0798 – A)

courtesy Robert Miller Gallery

More important are the lessons about fluid sexuality and the artists’ practice. Both Mapplethorpe and Smith became famous for art forms that were not their first endeavors. Smith was drawing and writing private poetry while Mapplethorpe was creating collages in the manner if not spirit of Joseph Cornell and Joe Brainard. On the cover of the memoir and within its pages, there are lots of photos of the gentle hippie Mapplethorpe. Long wispy air, a sly grin, and huarache sandals. A sweet man in the afterglow of the 1960s.

In that era, it was easier for a person to have relationships with both men and women. Even in the last year of high school, I remember chanting to my friends, “bisexual in the Bicentennial.” Moving along the continuum of sexuality grows more difficult as you get older and have an identity to project and later protect.

Before he became really famous, I heard Mapplethorpe lecture (if you could call it at that) at the San Francisco Art Institute. It was the only time I ever saw him in person. I remember he wore a khaki shirt and had his hair coiffed, not flowing the way it did in the photos with Patti Smith. He resembled a brownshirt from 1930s Germany, which I found more than a little disturbing. His photos of flowers were knife sharp, still new. If I remember correctly, he interspersed them with his sexual imagery. He showed some images that were even more brazen that the ones that later toured the country and caused all the outrage from the right wing. One of them was so daring that at first I didn’t know what I was looking at. The black and white image had the same perfect arrangement of forms as all his other still lifes. Then there was audible gasp in the audience as it dawned on them what they were looking at. With perfect timing, the image moved forward to that of an innocent child. A few people laughed, not because the next image was humorous, but because of the tension. Afterwards I think people challenged him, but he was imperturbable, untouchable.

After I finished Patti Smith’s memoir, I found Mapplethorpe’s exhibition catalog, The Perfect Moment, on the bookshelf. I think he used that phrase in his lecture. As if that search for some pure aesthetic moment gave all the images an equally emotional content of heightened experience. When I think of Mapplethorpe, I think of lost innocence racing towards the light.

On the one side, Armistead Maupin’s serialized Tales of the City captured the camp hilarity of the era, and on the other, people told tales of dumpster divers, dark dens South of Market, and three days running high. Mapplethorpe’s kinkier photos were like beautifully framed flashes into that underworld, photos that happened to end up in art school auditoriums and art galleries. The flowers, celebrity and fashion portraits, and kinks were all connected, but not in any obvious way. Despite his perfectionism, Mapplethorpe was an intuitive artist. He was following a search for the divine moment.

Perhaps Just Kids reminds us of an era when two artists were struggling with ambition and talent but without money or food, without strong sexual identities or images; when they were more like dancers, plotting, drawing, writing, and moving freely.

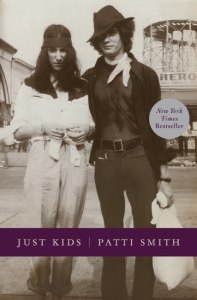

Patti Smith

ROBERT CHELSEA HOTEL 1970, 2009

Platinum print, ed. 1/3

10 x 8 inches, 25.4 x 20.3 cm (SMIH-0798 – B)

courtesy Robert Miller Gallery

Patti Smith

STRANGE MESSENGER, 2004

Oil, pencil and gauze on canvas mounted on board

91 1/2 x 92 1/4 inches, 232.4 x 234.3 cm (SMIH-0790)

courtesy Robert Miller Gallery

Note: You can see some of Patti Smith’s photo and drawings at www.robertmillergallery.com. She also has her own website at www.pattismith.net

You can hear a recent interview with Patti Smith at www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122722618

Robert Mapplethorpe’s images can be seen at his foundation’s site, www.mapplethorpe.org and at the Sean Kelly Gallery, www.skny.com