In 2011, I interviewed Henry Urbach, then the head of architecture and design at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), about the museum’s ParaDesign show. We toured the exhibit together, which displayed objects from the museum’s architecture and design collection that “question the norms, habits, and conventions of design.” The first half of our talk focused on the Tobias Wong show adjacent to ParaDesign. I never got around to editing the conversation or publishing the interview. When I heard that Henry had passed away on September 16, I decided to reread our conversation and share at least the first part of our conversation.

Q: I want to start first with the ParaDesign concept. When did you realize you had a collection in these objects?

Henry Urbach: I started to understand ParaDesign well before I came here as curator, because I had a gallery in New York, and one of my best clients was SFMOMA’s architecture and design department, first under Aaron Betsky and then under Joe Rosa.

They were buying things from me that were odd, that weren’t exactly architecture, that weren’t exactly design. We understood one another perfectly well. That’s when I first had the sense that the way I approach the fields of architecture and design had an intense affinity with SFMOMA’s approach.

Of course, the gallery worked with other museums and collectors, but SFMOMA really seemed to get this idea of interdisciplinary work, experimental, conceptual, critical. So when I came here as curator, it was very natural for me to continue developing the collection in that way, even while we have other more traditional points of focus, like iconic modern chairs and Bay Area graphic design and Bay Area architecture.

Objects in the ParaDesign exhibition. Photo: SFMOMA

But this thing remained at a subconscious, intuitive level for a really long time. And then about a year and a half ago, we made the decision to do something that had never been done at the museum before. We invited our accessions committee to a retreat.

The way it’s organized here at SFMOMA is there’s one accessions committee for painting and sculpture, one for photography, one for media arts, and one for architecture and design. We meet with our committees four times a year. The curators propose the works that we would like to buy or receive as gifts for the collection. And they vote. The votes are reviewed by the board.

I had been here for about three and a half years, and we all felt that we would do better to have a road map than to go meeting by meeting.

If you can say, “These are our strengths. These are our weaknesses. This is where we want to go,” then you have a strategy. We decided to launch that by preparing a pretty extensive quantitative and qualitative analysis of the collection.

We presented that analysis to our committee at this offsite all-day retreat and stumbled over this group of objects, most of which are in this room now, because they were “other,” they were miscellaneous. How can you say that a chair by an artist is furniture? Is it furniture?

We had the chance to discuss it at the meeting and come away and think more about it and realize that this isn’t a problem. This is really a strength. Let’s own it. Let’s name it. Let’s show it. Let’s put it out there, open it to debate. And that’s really what this show is about. It’s, if you will, a coming out for ParaDesign. It took us a long time to arrive at the name. And when we did, we felt it was just right, because “para-” as a prefix has so many meanings.

It really captures all of it without pinning anything down too much. So it’s works that are about design, around design, not quite design, aberrant to, ancillary to. All of these meanings seem to capture the works in this room in a way that we feel very comfortable with. I hope the artists and designers and architects do as well.

It reminds me of some of the discussions I had with the artists who showed with me when I had my gallery who had varying degrees of comfort with the gallery’s name, Henry Urbach Architecture. Some of them really loved almost the perversity of being an artist showing in a gallery that had “architecture” in the name. Some of them were a little more uneasy with it. But as those discussions evolved, it became clear to us and to the architects that what we were doing was really this hybrid.

And it was precisely that space in between, among the disciplines, where the questions we were all interested in were being raised.

Q: Tobias Wong has more works in this show than any other artist. What’s the chicken/egg with that?

Henry Urbach: As we were starting to think about ParaDesign, reviewing the collection for the most “para-” works, our review brought us to Tobi’s work. At that point we had collected four objects. He’s as para as they get.

In fact, he even called himself a paraconceptualist. And when we discovered that, that was a really lovely point of confirmation in a way. But of course this was all happening in I would say September/October [2010]. He had passed away at the end of May. And we realized no one had done an exhibition on his work yet. And this is going to be really hard, because we were in the middle of preparing the wine exhibition, and there was plenty else to do.

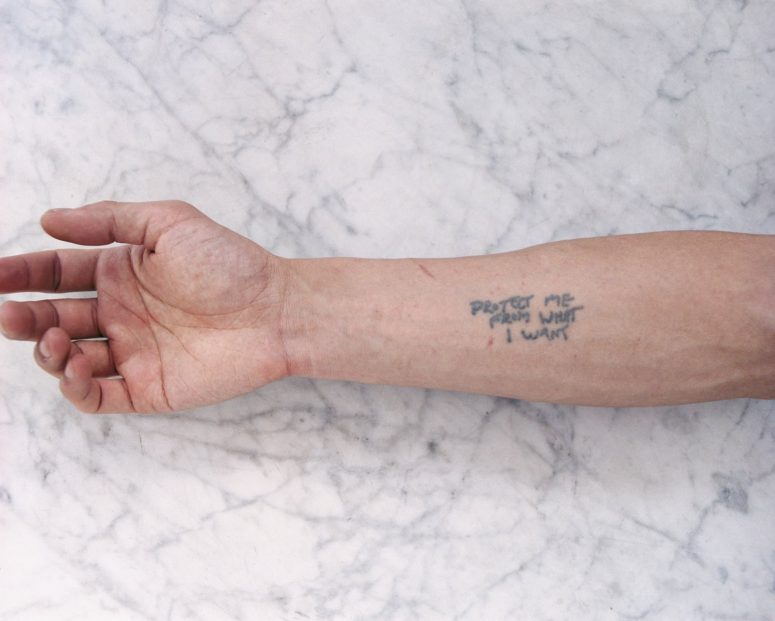

Tobias Wong, Protect Me From What I Want, 2002; artist tattoo. Photo courtesy SFMOMA.

Q: Had you already got this show underway then?

Henry Urbach: The concept was in place, but the design wasn’t done, the checklist wasn’t done. And we thought, wait a minute, maybe there’s an opportunity to do something more. What do we want to do? Is it a focus within the exhibition? Is it an exhibition within an exhibition? Or, as it’s become, is it a separate, adjacent exhibition?

We had a beautiful scheme develop where Tobi’s work would be more integrated with some of the others, but it involved a complex display system that wasn’t within our reach with our budget and schedule. We moved towards the separate exhibition, but also at the same time, it has to do with how we went from having four objects to the several dozen that are here.

So what was working in our favor is that I had these two contacts who knew Tobi. And they could help guide us to things. What wasn’t working in our favor is that his archive, if you will, his body of work, was not very well organized at that point. With many of the objects, it wasn’t clear to us if something was authorized or not, or a collaboration or not, or meant to be shown.

There was a team of three on these exhibitions. Me and two assistant curators, Joseph Becker and Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher. We all worked on everything, but Joseph took charge of the exhibition design and Jennifer took charge of the sleuthing. She became really a kind of private investigator. If you ever need a detective, Jennifer is the one, because she was indefatigable in hunting down information. For example, this piece, Transcendental Meditation, which was a collaboration that Tobi did with Amelia Bauer, a longtime friend, had been made before and shattered. So we contacted Amelia, and she was very happy to recreate it in the way that she knew Tobi would’ve wanted.

It also meant contacting Swarovski, who very generously gave us the crystals to make this new piece. Honestly, almost every object has a series of complex navigations and necessary negotiations. For instance, with Smoking Mittens [Final Home]. These mittens were designed and made by Tobi after Mayor Giuliani imposed the smoking ban in New York in indoor spaces. People were going outside to smoke, and it gets cold in New York. So it’s both unbelievably pragmatic and also very cheeky to produce these mittens that have a hole to hold the cigarette. Final Home was this sportswear, quasi-survival brand, and Final Home was [also] a reference to smoking. It’s all just so genius. But the initial research turned up another version of these mittens that’s actually in production and produced by a company called Suck UK.

Tobias Wong. Smoking Mittens [Final Home], 2003. Photo: SFMOMA

Q: Right. They make the Sun Jar that Tobias designed, the frosted mason jar with a solar-powered light.

Henry Urbach: This was just like one of those mysteries we had to solve: which are the real mittens? I think if he were listening to us right now, he’d be like, “Yeah, you’re damn right. I didn’t make it easy for you. You have to work for it.”

Q: Did he often both attract and repel us?

Henry Urbach: Yes. I think it’s something that’s so important, because in Tobi, I sense an ambivalence that I find very moving. It’s not an easy critique of consumer culture. It’s not an embrace either. It’s both at once. There is a complexity of things that would appear to be polar opposites but can be held at once.

Q: You see that in the paper cups he designed, illustrated with cut diamonds.

Henry Urbach: Yes. The trashy and the exquisite. This is an opposition that he explored again and again. This is a funny story. I don’t know if this should go in print. But Tobi made these pearl earrings that he dipped in rubber. The images that we have of them show a Tiffany box. So we had the earrings, and they didn’t look right on this reflective black Plexi. And the image showed a Tiffany box, but it didn’t come with the loan.

So it was my job to go over to Tiffany’s in Union Square and try to score a box. I presented my card, explained who I am, explained what Tobi did. And the manager said, “Absolutely not. We will not give you a box or a bag.” Presumably because they don’t want people giving costume jewelry in Tiffany boxes, and they’re protecting their brand.

I said, “Well, would you consider giving me a pouch?” which is actually what I really wanted anyway. It has more intimacy. And she said, “Oh, yeah. There’s no policy against offering the pouch.” So that’s really nice. And the way we’ve displayed it, we’ve tried to block the name a little bit because we want to respect their corporate concerns, but the blue itself says it all.

Q: All my earrings come in pouches.

Henry Urbach: There was a pentagon sofa—I think Jennifer and I spent close to a full week trying to understand what happened to this thing, because in fact Paola Antonelli [senior curator of the department of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City] organized a show in Brazil, and this was produced [for that]. But it was held up in customs and then burned.

We went to the manufacturers in Vancouver, who are also longstanding friends and collaborators of Tobi’s, and they were up for making it and giving it to us. But there wasn’t enough time. They would have been able to do it if they could have found the maquette that they could’ve passed on to the craftsman. But the maquette was missing in action. In the end, it’s not the same as having the object, but it’s great to have the image and realize that this guy, soon after 9/11, imagined the idea of a pentagonal sofa that would go along with luxury and consumer culture. This is the other great theme of his work: the interplay of anxiety and material objects and how we use objects to feel safe.

Not only is the Pentagon a symbol of power, but it also happens to be the one building in Washington, D.C., that was hit during 9/11. But then it doesn’t carry a tragic or melancholy quality, because in fact it’s reinvented, so the sofa becomes this wonderful social space that you haven’t been able to imagine before in this way.

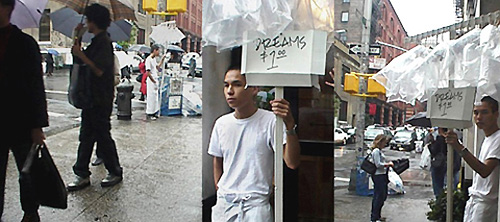

Or this photo?, which depicts, as far as we know, Tobi’s first public act while he was a student at Cooper Union, where he stood on a corner in SoHo in front of a shop called Fake and sold bags of air with the sign “Dreams, $1,” already riffing on other artists—David Hammons with his snowballs, for example. And Tobi was a master of appropriation. Oh, not only shameless, but absolutely proud and canny about it.

The whole notion of originality, authorship, artistic genius, was so, I think, passé to him that it allowed an unbelievable genius and originality to emerge. I heard from Amelia, his collaborator on Transcendental Meditation, that in 2005 he declared that he would no longer produce objects on his own, only with collaborators. And he tended not to work with the same collaborators very much. He was a serial collaborationist.

Tobias Wong. Dreams, 1999. Photo: SFMOMA

Q: Now, what is this? I forgot.

Henry Urbach: This is another collaboration with Amelia Bauer and Swarovski that was presented at the 2005 Art Basel Miami Beach fair in the Swarovski booth, where Swarovski crystal created a chandelier suspended in a tank filled with piranhas. I mean, just so genius, right? And yet with something like this, as a curator, you have to ask a question. Because to reproduce this, sure, it can be done. We have the technology. But it’s so much about the context. It’s so much about a design fair in Miami around 2006, when there was this feeding frenzy. That’s what he’s commenting on. And so his work really raised some very interesting, tough, and engaging curatorial challenges for us. I will say that I didn’t understand this until the day that we opened the exhibition, because we were so immersed in this forensic process and trying to persuade our colleagues here at the museum that we weren’t completely insane trying to bring an object in four days before the opening, like, “Please bear with us.”

We really tested a lot of people’s patience. But as I said, I was obsessed. I was determined. And what I didn’t realize is that we created a shrine. It’s not as much an exhibition. It’s certainly not a retrospective. It’s not even that accessible in terms of knowing in traditional museum terms, like, “This followed this, or this was influenced by so-and-so.” It’s not that. It’s a shrine.

And in the shrine, we have something like a body lying in state, which is the bulletproof duvet cover that he made. Again, this theme of anxiety, security, using a very traditional craft technique of stitching, but with the ballistic nylon to protect the body. And then lined with felt. On the other side is the other ballistic piece, Ballistic Rose, which is such a genius idea. It’s oversized to cover the heart. Is it really protecting the heart from a gunshot? Or is it protecting you from a broken heart?

Q: Right.

Henry Urbach: And the blackness of those objects. It’s interesting, because we arrived at the decision to use, in ParaDesign, a black wall at the end to demarcate the space and also to provide a strong backdrop for An Te Liu’s Cloud.

Then we realized this wall should be black. It reinforced that idea, and very, very late in the game, we decided to position these two critical pieces at the entry, this luscious prismatic, chromatic piece that’s full of life and energy and then the last piece he made, New York I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down, which is the title of an LCD Soundsystem song. He exhibited it at the International Contemporary Furniture Fair in New York, I think, for 10 days or so before he died. It spells out the title of that song in Morse code. So, almost a coded message to us, to the viewers. “New York, I Love You but You’re Bringing Me Down.” That same ambivalence again.

It’s love and hate at the same moment. It’s passion and anger at the same moment. We grouped that with this wonderful piece called Casper. It’s spelled “Casper,” but apparently he insisted that it be pronounced in the French way, “cas-pair.” He takes the classic form of a pillar candle in a lovely cut crystal candleholder and recreates the candle as a glass tube so that you fill it with oil. It’s ghostly.

Tobias Wong. Casper, 2003. Photo: SFMOMA

Q: The other thing is that Casper changes completely whether you’re standing here or there, because here it’s silver because it’s reflecting the white. But there it’s black, because it’s reflecting the black. It changes utterly, which is interesting.

Henry Urbach: Maybe in terms of exhibition design strategy, which Joseph Becker, the assistant curator, took the lead on, we wanted to suspend the rules so that you would know the rules better. That’s the idea of ParaDesign as a critical mirror to design. If you study yourself, you know yourself better. If design studies itself, it knows itself better.

More information

https://www.sfmoma.org/exhibition/ParaDesign/