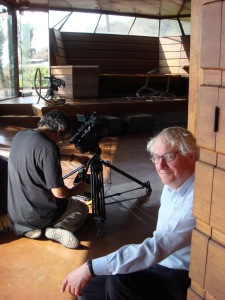

Director Murray Grigor

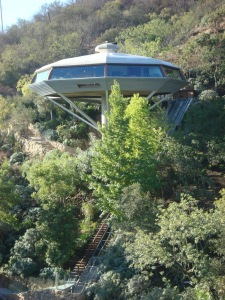

Turner House, Aspen, Colorado

I only met Lautner once in Los Angeles and he said then (and repeated often) that he hated that city, but it was the only city where he could find clients who would let him do what he wanted. His lessons were not for the architect concerned with social equity. Few people will ever visit Silvertop, or the house overlooking Acapulco Bay. Yet, he inspired thousands of architects (and architecture students) to realize that a building emerging from a dream could be built. This film may be as close as we get to experiencing such spaces.

After the recent screening as part of the AIA’s Architecture and the City Festival (www.aiasf.org/archandcity) we joined curator Erin Cullerton, director Murray Grigor, and producer/editor Sara Sackner for dinner at Heaven’s Dog (http://www.heavensdog.com/). It was an evening of laughter and tales of making movies (Murray just completed a film about the British designers, Robin and Lucienne Day), and listening to Murray impersonate his long time friend Sean Connery. The evening was over so fast I had forgotten to ask the movie makers a single question. I followed up a few weeks later.

Since the screening, the City of Beverly Hills has approved demolition of the Shusetts House, one of Lautner’s early houses. Hopefully, more people will see the film and understand the significance of Lautner’s work.

Q: How did you choose Lautner as a subject for a film?

Murray: Lautner chose me, or at least Nicholas Olsberg did. As far as I understood, Ann Philbin, Director of the Hammer Museum, had invited architect and Lautner scholar Frank Escher, and thus Nick, to curate a Lautner architecture show. Both realized that Lautner’s buildings would be better experienced if filmed sequences of key works, rather than photographs, were displayed to complement Lautner’s large models, renderings, plans, and sections.

This was an idea Nick and I had hatched when he was the director of the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal, when Mildred Freeman was curating the 1999 exhibition about Carlo Scarpa, Intervening in History. In the end, the CCA chose photography over cinematography, although many of the planned sequences were incorporated in my film, The Architecture of Carlo Scarpa, which came out before the exhibition in 1995.

Q: You have a little bit of biographical information about Lautner, but you mostly stay away from the personal in this film. Why is that?

Murray: Infinite Space was always planned, as its subtitle suggests, to be The Architecture of John Lautner. This was the aim in my previous films, such as The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, which concentrated on Wright’s career as an architect, but only touched briefly on his family dramas.

Q: Did you know much about Lautner when you started the project?

Murray: Thanks to a US/UK Bicentennial Fellowship in the Arts I moved to Los Angeles in 1977 with my family, and stayed for a little over two years researching the Wright film. I joined The Society of Architectural Historians, Southern California chapter early on. I was lucky enough to carpool with the great UCLA historian, Tom Hines, who would soon become my advisor on the Frank Lloyd Wright film.

On many excursions I got to know the extraordinary wealth of innovative architecture in the Los Angeles area. Esther McCoy took us on a tour of the Case Study homes. Soon Ray and Charles Eames were helping to steer me to Taliesin. For our last six months we housesat at a film director’s home in the Hollywood Hills, close to the Chemosphere House, which, along with the Googie coffee shop next to Schwabs on Sunset Boulevard, first introduced me to Lautner’s work.

Chemosphere House, Los Angeles

Q: Over time how did your perception of Lautner change?

Murray: In the mid-eighties I directed an eight-part Mobil PBS series on American architecture with Robert A.M. Stern titled Pride of Place. Lautner was just Googie architecture to Bob. I soon found that the East Coast consensus was really down on Lautner – with some really hurtful articles written about his work. I had always admired the writings of Peter Blake, but found that he was the most critical of all. Blake really hurt Lautner when he described his work as roadside junk that was poisoning the landscape. The fun and joyous elements were missed and Lautner’s inventive spaces were disregarded.

That’s why for this film we interviewed David Wasco, the production designer who worked with Tarantino on recreating the Lautner spaces in films such as Pulp Fiction. Wasco celebrates the fun and joyous elements of Lautner’s Googie architecture.

Q: Do you feel that his architecture elevates building into the realm of art?

Shooting the Pearlman Cabin in Idyllwild

Marbrisa, hanging over the Bay of Acapulco, shares the little Pearlman Cabin’s DNA, though it far exceeds it in scale. The same overriding roof is there, but here it seems to be a floating cloud of concrete.

In the warmth and gentle breezes of Marbrisa, both the logs and glass are gone. There’s no facade – just an anchored view over the sea into infinite space.

Marbrisa, Acapulco

Marbrisa, Acapulco

Q: What insights did the clients offer?

Murray: In our film we were lucky to have included Donald and Octavia Walstrom, who were very much a part of their home’s genesis.

Donald, like Leonard Malin of the Chemosphere House, was an engineer in the aerospace industry and helped build the house and invented some of its gadgets, much to Lautner’s delight.

After getting over the shock of Lautner’s proposal – a house on a concrete stalk – Len Malin conspired with the great boat-builder, John de la Vaux, to triumph over Los Angeles planning restrictions.

At Silvertop, the partnership between inventor Ken Reiner and innovator John Lautner made for the most fruitful collaboration.

The tragedy was that Ken lost his home, then close to completion, when his partners forced his company into bankruptcy.

Q: Were these clients’ lives changed by Lautner’s designs?

Murray: They were, especially those like the Walstroms, Pearlmans, and Malins who had helped build their homes. Those who rescued homes from the wrecker’s ball, as Kelly Lynch and Mitch Glazer did, have been rewarded by the sublime spaces they now live in. Kelly and Mitch did a lot to raise awareness of Lautner’s importance years ago when their inspirational rescue was featured in Vanity Fair. Mark Haddawy has rejuvenated Lautner’s first Harpel House by going against venal real estate logic. Losing a bunch of guest bedrooms he took off the accretion of an upper story, and restored the home down to the last hinge. Mark has achieved a masterful lesson on how homes designed by a master, when returned to their original plan, can become treasured works of art.

Murray: The kindness of the original clients, and all the new owners, who let our camera and our cumbersome equipment into their beautiful homes. They all shared with us the insights they had in the adventure of living in the ever-changing light of Lautner’s magical spaces.

Q: How did you get Sean Connery to return to the Elrod house?

Murray: That, I am afraid, was achieved through smoke and mirrors. I had co-authored a book on Scotland with Sean – called Sean Connery – Being a Scot. The cinematographer Hamid Shams and I were down in Sean’s home in the Bahamas to produce a short video to promote the book at the Edinburgh Book Festival. So after a fun day doing that, Sean recollected his experiences of the Elrod House for us in his study. Hamid’s brother Farad is a genius at digital manipulation, and was able to seamlessly substitute the backdrop frame by frame, with one of Sara Sackner’s photographs of the Elrod House. Because so few people have so far heard of John Lautner – even though many have seen his homes as backdrops in Hollywood movies – it seemed an obvious choice. In Diamonds are Forever the Elrod House had only recently been built, with everything in pristine condition and no clutter. Not to mention 007 himself, who defined the periphery of Lautner’s great domed space like the panther that he was.

Q: What did you cut from Infinite Space that you wish you could have included?

Murray: Nothing of any real significance was cut. After paring down our list of homes we stuck to that and they are all in the final cut. The DVD also has the seven film loops which ran in the Hammer exhibition, along with insights by Frank Escher.

Q: Do you have a favorite Lautner house?

Murray: The Pearlman Cabin in the woods of Idyllwild, because I can imagine it would even have been affordable.

All photos by Sara Sackner, www.paddedcellpictures.com

Further Research:

The website for the film is www.infinitespacethemovie.com

The website for the Lautner Foundation is www.johnlautner.org