Richard Serra Drawings: A Retrospective

Sharon Lockhart: Lunch Break

Earlier this year, we saw “Richard Serra Drawing: A Retrospective” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It was sparsely attended compared to the Alexander McQueen extravaganza in the gallery next door, which was breaking records. Seeing both exhibits in the same day was a kind of mental jujitsu.

The Serra show moved to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art this fall, and it works better here because of the generous space each piece is given and the daylight from the uncovered skylights (my favorite detail in the Botta building). The curators have placed a complementary if very different show in the adjacent gallery. Sharon Lockhart’s “Lunch Break” draws from some of the same roots as Serra—the ironworks and the shipyard.

Both artists might be labeled conceptual, but that’s just an easy term for someone playing with concept over object. Lockhart’s piece is an 80-minute film that stretches out a ten-minute walk through a corridor during a lunch break at Maine’s Bath Iron Works. There are also a few stills of the evidence found along this walk.

Serra’s show focuses on several large drawings made with ink stick as well as some sketchbooks and selected sculptures from SFMOMA’s collection that were not in the New York presentation.

Richard Serra was born in San Francisco, and his father worked in the shipyards here. Serra himself worked in steel mills as a young man. As America’s industrial age reached its height before the space age, great ships, submarines, and other structures were some of the country’s mightiest accomplishments. Both artists use this as a source for their work, albeit in different ways.

In his early sculptures, Serra placed pieces of lead against a wall or each other, defying their apparent weight. Molten lead flung into the place where the wall meets the floor feels both liquid and solid. Something as heavy as Cor-Ten steel or lead can feel almost weightless. Think of an enormous battleship at the moment it is launched. It floats. This apparent contradiction speaks to the central condition of many of Serra’s experiments. Likewise, black ink stick can help you see light and space.

|

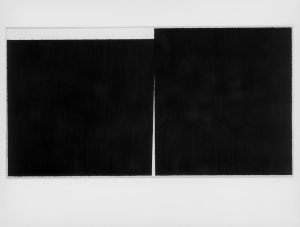

| Richard Serra, Solid #13, 2008; paintstick on handmade paper; 40 x 40 inches; private collection, New York; © 2011 Richard Serra / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo: Rob McKeever |

The recent Serra sculptures that I saw this fall at the Gagosian Gallery in Manhattan convey, at first, a kind of somber heaviness, but they also inspire children to run in delight. After spending most of an hour wandering through and around them, I relished the feeling of being lost. I was giddy. I have actually begun to dance inside the sculptor’s “Torqued Ellipses” at Dia:Beacon.

All of the works in the current drawing show are black. But I felt that the color was not symbolic. Many of the drawings work like sculpture, using edges to define and redefine space and alter the perception of volume. Within the space of the piece entitled “Union” (recreated for the specifics of each space where it is shown), I moved back and forth, trying to place myself. Self-generated movement is also a key part of Serra’s work. If you let him, Serra can slow you down long enough to really experience your body in space.

Across the way, Sharon Lockhart’s film also slows the viewer down. Few people can sit through all 80 minutes of her film at one go. I viewed the film for a few minutes each time I was at the museum during the last few months. Film, that medium that has speeded up our lives, can also be used to accomplish the opposite. Lockhart never condescends to the ironworkers, but rather cherishes them. Workers with these skills are also helping to create Serra’s sculptures. Both exhibits give us a fuller picture of our contemporary life, even as both the picture and the memory transform into a memory.

Both shows are only up until January 16.