I almost skipped my high school graduation. There didn’t seem to be any point. During my four years, I got into the novels of James Joyce, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and William Faulkner and a project about King Tut’s tomb, and that was about it. Ever since middle school, I’d only wanted to attend the famous British “free” school, Summerhill. Since that wasn’t going to happen, I sulked. Yes, it was a little bit more complicated than that.

Our 1976 bicentennial graduation was held in Richmond, California’s Memorial Auditorium, part of a brick moderne complex designed by Timothy Pflueger, restored in the last few years. (I used to say, “bisexuals in the bicentennial!”) Going or not going to graduation didn’t matter to me. Most of my friends were going to college. All I wanted to do was move to San Francisco. Didn’t even bother finish a single college application. So when the acceptance from San Francisco State University arrived, I was surprised—and angry.

And that’s what a privileged jerk I was. SF State cost around $90 a semester to attend, and I felt like I could walk away from it—that it wouldn’t make any difference to my pointless life. By then, my parents were so tired of my nihilism and depression that they just didn’t want me hanging out at home doing nothing, so my dad had filled the forms out and forged my name. Not sure they understood that hanging out at home wasn’t on my agenda. There was another life waiting across the bay.

In the 1970s, most middle class kids in California went to public school. A few families sent their kids to Catholic school. I don’t think any of my pals went to boarding school. California’s Proposition 13, passed in 1978, changed that landscape. California went from having the best public school system in the country to having one of the worst. It was the dismantling of a public agenda. What bothers me now is that I wasn’t aware enough to see that I could have learned more if I’d understood the purpose and ideals of a public education. Looking back, I think it was a combination of depression, no idea of philosophy, and a hatred of all things authoritarian that made my young life so miserable.

This last weekend, we went to Tucson to witness the daughter of our good friends Miguel and Sonya graduate from high school. The very same Catholic high school where Miguel graduated from. His parents grew up and received their educations in Cuba. They had supported the overthrow of Batista but became quickly disenchanted with Castro and escaped to Miami, San Antonio, and eventually Tucson. Tucson was growing in the early 1960s, and young immigrants with educations could get professional jobs. Miguel’s family thrived.

We first knew Miguel and his wife when they lived in Berkeley in the 1990s. They returned to Tucson because of opportunity, the relative low cost of living, and, of course, family. At first, I thought they were moving back to Tucson because they were so focused on their careers, and the grandparents and extended family could help with childcare. But I didn’t understand the pull of a large close family who had migrated under adverse circumstances. My immediate family is small and polite, but not intimate, and our mother didn’t encourage us to be friendly with our cousins (on either side of the family). Family was a once-a-year thing. Summer visit for the Oregon cousins and Christmas carols and punch for the Santa Clara cousins.

The night before the Tucson graduation, there was an informal gathering at Miguel’s parents’ house. Even Miguel didn’t know everybody’s name. I always enjoy a few moments with his mother, because she will share some small story about the family from before we knew Miguel. If you ask a question about Cuba, you are in for at least 20 minutes. But this time, she talked about being 84 and having to move to her daughter’s house soon. She laughed and said she’d known this would happen around 80 but was thankful for the extra four years. She also knew that this was the last large party she would host in her own house.

For graduation, we had two tickets but no assigned seats at the Tucson Convention Center, an unfortunate piece of brutalism that destroyed a downtown neighborhood. We were told to arrive early because of parking. No surprise in an auto centric town. We parked in the Barrio historic district, risking a ticket for staying more than two hours. Inside the vast arena, we were greeted by fried food smells and hawkers with blue lemonade and popcorn. Reminded me of going to the circus when I was a kid. Right away, I wondered why fewer than 300 graduates needed an arena that sits close to 9,000 people.

Watching the arrival of families was telling. The arena hosts conventions and has booked acts like Ike and Tina Turner and Elvis Presley. But today, most folks were dressed as if they were going to church. Although there were several empty seats, we soon realized that entire rows were being saved. One well-dressed kid sat one seat from away from me to hold down the rest of the row. Although the entire arena was not filled, it was clear that each student had their own entourage of literally dozens who would shriek when their name was read. It was clear from reading the program that the entire class had been accepted to college. There was a lot to be proud of. Most of the names were Hispanic.

This Catholic school has its roots in the Order of Carmelites. The various speeches by faculty and students avoided any controversy. Given the high school shooting the day before in Santa Fe, Texas, this seemed odd. If there was one theme, it was kindness, and that felt like an authentic call. Paul joked it all celebrated Saint Platitudes.

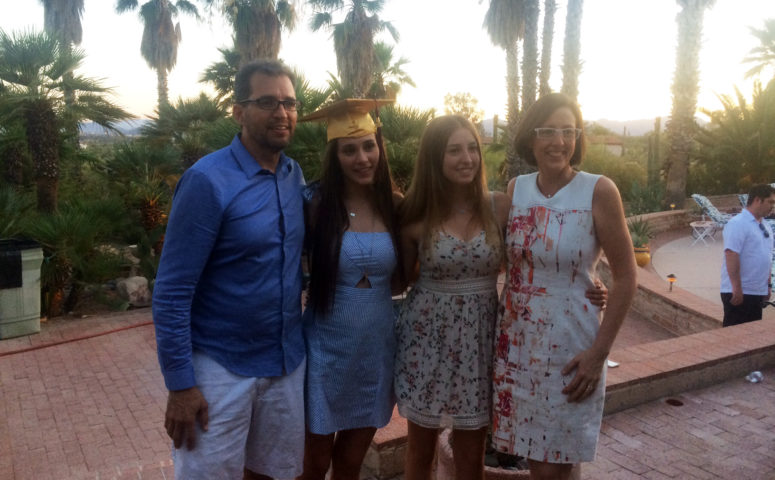

Afterward, there was a lively party at Miguel’s sister’s house in the foothills. This is a neighborhood where the roads are still unpaved, and the desert hasn’t been trampled under asphalt. Little kids splashed in the pool, and even an adult or two got wet. When it was time for family photographs, almost the entire party gathered on the terrace.

Then it all hit me. The infrastructure of family here offers support and encouragement but also carries expectation. Our family wasn’t really like that. I stumbled through my youth without a mentor. My family couldn’t wait to disperse, but other families form a net that can catch members when they fall while also letting them grow. The second generation of this family in America has taken root.