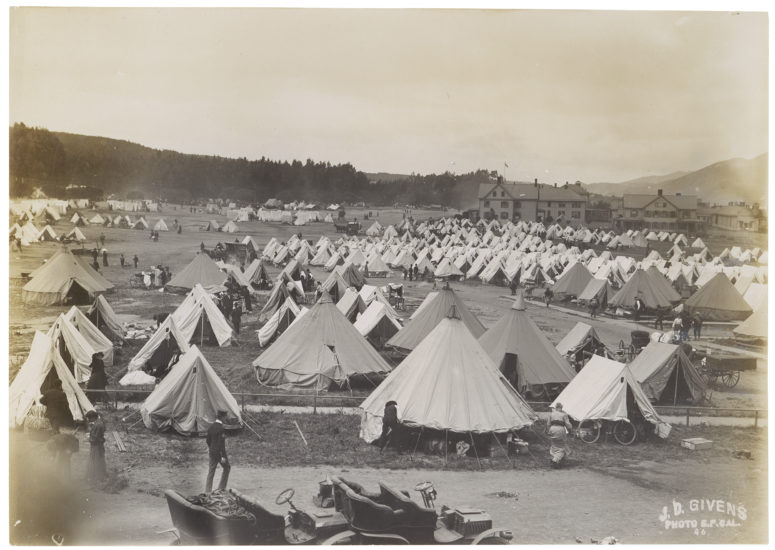

After the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, many people moved into tents in Golden Gate Park. Much housing was uninhabitable, and open areas were a safe alternative. Today, people are moving into tents on public land again, under freeways and in public parks—this time in a manmade rather than a natural disaster.

Tents in Golden Gate Park following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Records of the United States Senate, National Archives.

Paul and I are fortunate enough to live on the ninth floor of a high-rise overlooking a park in Oakland. We are just above the tree line, with a view of a Lake Merritt. We do hear late-night noise from revelers of all kinds, and early in the morning, we hear the various squawks and burps that utility vehicles make as they emerge from their sleeping place tucked in the middle of the park. Small cost for a bucolic view in the middle of an urban setting.

Recently, a few people moved into the park. One or two people set up a flimsy construction at the edge of the park, almost on the street, right beneath our windows. It looked fairly unsafe, and within a few days the police removed them.

Last week, a group of tents, similar to those used by Boy Scouts, appeared inside the park next to the maintenance yard fence, arranged neatly and relatively clean. Unlike the tent cities underneath the freeways, this one doesn’t have refuse lying around. It is unclear what the residents do about showers and bathrooms.

Since our building had sent out a flyer urging us to call the city to have the tents (and the people) removed, I decided to look in on the tiny tent town.

The view from our condo.

Last Sunday was windy and clear. In front of the encampment is a table set crosswise to serve as a bar, with a fresh multicolored blanket across it, and there is a protest banner on the ground. Behind the bar is a curtain of sorts to serve as a second barrier before entering the courtyard formed by the two main tents. The setup works like a courtyard house in Mexico or Latin America. Within the courtyard, I found two men, both of them willing to talk once they determined I was not there to cause harm. They welcomed me into the inner space and asked if I wanted coffee. I shook their hands and said I lived in the building next door.

Both men introduced themselves and asked if I was a representative of the building, and I said no, I was not there in any official capacity. I told them we had received a flyer telling us about their encampment. They both knew that the mayor’s mother lived in our building, but neither spoke ill of the mayor or her mother.

To be honest, I was afraid of talking to them. I live in a bubble of privilege. They are, indeed, to some degree, the “Other.” But I felt it was important to meet them, and I spent perhaps 15 or 20 minutes talking to them. They were not dirty or unkind. The older man appeared to have set up camp first and saw himself as a leader. He talked about the need for fire circles and sweat lodges all around the lake, for places where people from all backgrounds could come together. Somehow this would culminate in a fantastic gathering in New York City on Thanksgiving Day. The younger one spoke more about local development and the need to give apartments to the homeless. Both of them said they were keeping drug addicts away from their encampment. I offered them some bananas and a loaf of bread.

One small step we can take is to not see people immediately as the Other, as someone to be removed by the police. Any one of us could get addicted to drugs, fall off the economic prosperity wagon, or have a breakdown. One of the reasons we make the homeless the Other is so we don’t have to face our own vulnerability.

In Golden Gate Park, the 1906 tents were replaced by cottages, and eventually people moved into newly built housing or even moved their cottages to empty lots. The new tent dwellers are not so lucky, because there is no end in sight. In the meantime, I am not going to call the police to remove them without any safe long-term place for them to go. But I might call on my local elected official to find a place where they will be safe with access to the services we all need, and only some of us receive.

The economic crisis we are living through won’t pass until we change our thinking about compassion and capital.