We went to Seattle to see Ann Hamilton’s show at the University of Washington’s Henry Art Gallery. Since her art is all encompassing, and it was our first major stop after lunch at Café Campagne, she gave us the lenses for the weekend.

We rode into town from the airport on the Link Light Rail, which just started running in 2009. When you are excited to get somewhere, it takes too long. Although Seattle is famous for the monorail left over from the 1962 World’s Fair, it never really went anywhere. Link is the fulfillment of the promise—47 years later. The ride goes high in the air, underground, and on city streets, and in truth, it only took us half an hour once we got on the tram. It costs a lot less than a taxi or an Uber. On the map, it looked like a short eight blocks to the Sorrento Hotel. Short but mostly uphill. By the way, the Uber drivers in Seattle are not as good as the ones here. They just don’t know the city. I still think using Uber beats dealing with the hassles of a rental car, though.

The Sorrento Hotel was completed in 1909, just in time for the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition that landed Seattle on the map. (The fairgrounds are now the site of the University of Washington.) The hotel is a bit like a rich grandma’s apartment. Some of the improvements have been questionable, but you love her anyway. They have a wood paneled bar and lobby (known as the Hunt Club), fantastic sheets and towels, a powerful shower, and fresh ground coffee with a French press in your room instead of that dreadfully weak plastic coffee most hotels have. Should you arrive in a carriage, they also have a huge porte–cochère.

Just before visiting Seattle, I read Martin Pedersen’s short piece on Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building discussing how the landmark was a catalyst for many second and third-rate imitations (http://www.fastcodesign.com/3042844/hate-your-soulless-office-tower-blame-the-seagram-building).

Olson Kundig’s Pike & Virginia Building (designed by Jim Olson, Gordon Walker, and Rick Sundberg) from 1978, in the Pike Place Market, seems to have served as a model for the recent multifamily housing boom in Seattle. Boxy is good. What the new buildings lack is everything their predecessor possessed, like quality materials, volumetric variation, and a keen understanding of both immediate and distant context. Central Seattle has densified, but at a huge cost. Belltown and other central neighborhoods are suffering from a rash of truly mediocre buildings. It is as if somebody legislated corrugated metal and grey Mondrian patterns. This town needs some serious design review.

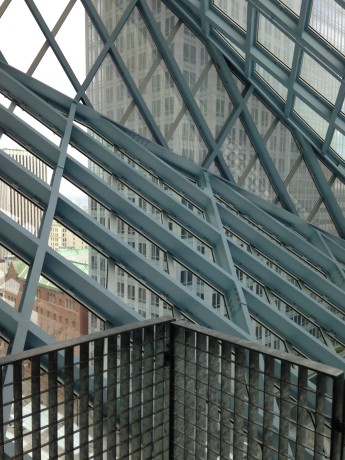

Seattle has, for the most part, been a conservative city when it comes to modern architecture. There are notable exceptions, such as John Graham and Victor Steinbrueck’s Space Needle and Minoru Yamasaki’s Federal Science Pavilion from the 1962 World’s Fair. And of course OMA’s brazen new public library and Steven Holl’s exquisite Chapel of St. Ignatius at the University of Seattle.

One of the city’s best modern works is Lawrence Halprin’s Freeway Park, which remains a security challenge. Even Microsoft founder Paul Allen didn’t seem to have enough money to get a first-rate Gehry building—his EMP Museum is universally disliked. And of course Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates’ Seattle Art Museum is basically a postmodern relic, with its staircase to nowhere recalling the famous freeway to nowhere that ran through the Washington Park Arboretum and the monorail to nowhere that runs a few blocks from Westlake Center to Seattle Center. There are several midcentury gems by folks like Paul Hayden Kirk throughout the city, but they tend to be domestic in scale.

All of that said, Seattle is a city that’s easy to love. Who cares about mediocre buildings when you have vistas of waters and snowcapped mountains at every turn?

Although I am not a big fan of Brad Cloepfil’s new addition to the Seattle Art Museum (referred to as SAM), I have seen some good shows there, including one on Nick Cave a few years ago. Right now, there is a tiny show on Duchamp that I walked right by. How Duchampian is that? There was also a small show of SAM’s collection of Joseph Cornell boxes and collages. which always seduce me. The blockbuster show is Indigenous Beauty, which can be enjoyed by the scholar and the casual visitor alike. http://www.seattleartmuseum.org/exhibitions/indigenous

SAM’s big design triumph has been the Olympic Sculpture Park (Weiss/Manfredi), which straddles a highway and railroad tracks to take you from Belltown down to the water. This is my third visit to the park, and I liked it more than ever. The entry building leads the pedestrian in and along the path to the sunken court and Richard Serra’s Wake from 2004.

This is one foodie town. We had superb meals at Anchovies & Olives, Matt’s in the Market, and Oddfellows Café and Bar. Fresh, not too fussy, although there was a bit of almond foam accompanying my scallops at Matt’s.

But we came to Seattle for the Ann Hamilton show at the Henry Art Gallery. Hamilton had an earlier show here in 1992 before Charles Gwathmey added his mostly subterranean addition. The title of this exhibit, Ann Hamilton: the common S E N S E, refers to touch: solitary touch, lost touch, and touch right now. Hamilton herself culled most of the objects in the show from the university’s various collections. Curiously, there are few objects to actually touch in the show. Touch becomes a construct for the viewer to understand and assemble. Each visitor is offered a folder, which they can use to assemble a kind of common book for their reference. This is a show where you are encouraged to both take away and give something.

Just beyond the front desk is a gallery where a friendly assistant explains the process of collecting parts of the exhibit and tells you what you can offer in terms of a written text and your own photo. Each of us leaned into a scrim, and now we are somehow part of the archive of the exhibit. (These photos are not available to take away.) One day, we will be on a wall somewhere with all the many dead animals, or in a case with furs and feathers worn by local Native Americans or the white immigrants who occupied the land later.