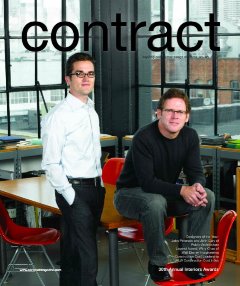

On January 30, architects John Peterson and John Cary were named “Designers of the Year” by Contract magazine. They are the first design professionals to receive this honor for their work as advocates within a nonprofit rather than as members of a design firm.

Their reach extends further than most designers. Public Architecture (www.publicarchitecture.org) feels that design can help change communities and in turn change itself. See the video that this interview was conducted for.

The conversation took place on Election Day, before we knew that Barack Obama was to be our next president. Public Architecture’s commitment to service resonates with the country’s new era. We thought you might enjoy the longer conversation in which they explain the organization’s founding, projects, and philosophy.

Q: Every year, the Designer of the Year is asked what the word “design” means to them personally.

John Peterson: In the broad range of possible activities on the planet, design is a marriage between art and technology and the creation of things. There is some balance between the technical and the artistic.

John Cary: I think design is what really makes things, be they objects or experiences or spaces, unique and distinct from the next. At Public Architecture, we are bringing design to people and places that wouldn’t otherwise benefit from it. Right now, design suffers from a kind of class issue. It costs money to get things or places that are truly well designed. And that’s one of the barriers we’re trying to break down.

Q: Does that mean the democratization of design is in America’s future?

Q: Does that mean the democratization of design is in America’s future?

JC: I think what Public Architecture and groups like us are trying to do is truly democratize design in a way that still maintains all the lofty goals and expectations of the design professions that we were all attracted to in the first place, but brings it to a much broader audience.

Q: Where did your interest in socially conscious design come from? Did faith have much influence on you?

JC: I came into this line of work somewhat unexpectedly. I went to undergraduate and graduate school expecting to be an architect. But somewhere along the way, I got interested in the politics of the profession. And my exposure to that revealed to me the limits of who the design profession really serves at any large scale.

As I began to think about this more over the past few years, it has occurred to me that I’m the son of a 30-year nonprofit executive director. And while I was raised in a quite religious family, my interest in social justice and those kinds of issues is totally distinct from religion and faith. But if you compare me to the way that John Peterson came into this, there is a very strong thread from my early days of architecture school all the way through.

JP: We did come at this from a couple of different platforms. I really was committed to design work, in many ways, for itself, and very interested in pursuing design work independent of its political consequences, which I have come to believe was an adolescent idea. Look, architecture is very political, whether you accept it or not.

I really came out of a tradition that was primarily focused on design and was independent of the social ramifications of the work. That has really colored the nature of Public Architecture. We have not positioned ourselves to somehow be separated from the progressive design community. We’ve always seen ourselves from day one as bridging the worlds of progressive design and a socially progressive group of designers.

Q: Do you see this work as an alternative career within architecture?

JP: I don’t see this as an alternative career for me. We are a nonprofit organization instead of a for-profit organization. In many ways we are doing many of the same things you do in a traditional design firm.

This is just an extension of the work that I found most engaging. My work changed its nature based on my growing interest in looking beyond aesthetics. The trajectory of my own architectural design thought included things like social responsibility, social justice, socioeconomic issues, and political issues.

At the same time, I understood that I was not a unique designer in this regard. If I was having those feelings, other designers were also probably having those feelings, and there was an opportunity to really capture the will and imagination of the design community as a whole through this sort of change in interest.

JC: That question has haunted me from the very moment that I started my career, and yet, for me, it wasn’t an alternative to anything – it was the career that I felt I was prepared for, that I was interested in, that I was passionate about.

The “Designer of the Year” designation is important in that we are being recognized for everything we’re doing, whether it’s program management, development, project delivery – because it all involves design and it is designed.

JP: John’s generation is going to change how we look at a design career, and his generation is not going to put up with the narrow view that earlier generations did.

Q: I think you are being recognized, at least in part, because you are trying to help communities in a concrete way, but also change the way architecture sees itself and eventually the way design might be perceived in society. So how can architecture and design inspire the general public day to day?

JC: Very early on in the development of the organization, we got a really profound taste of how design can inspire the public and what that means for us as an organization.

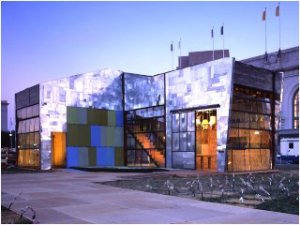

This was through the design and construction of, and ultimately the broadcast of a National Geographic Channel documentary about, our ScrapHouse project. This was a project that we designed and constructed over the course of just six weeks as a temporary demonstration home. It was a house built, essentially, of garbage, in front of San Francisco City Hall.

During the period that it was under construction as well as the four days that it was open to the public, we welcomed over 10,000 people from all walks of life to experience a different kind of architecture, which took risks. Yet it made people feel good, even though they were experiencing something new and unique.

Q: Let’s talk a little more specifically about Public Architecture. What was the evolution of the organization?

JP: It began with my private practice. We were fortunate to have a number of good residential commissions. But I think there was a level of pent-up energy around participating in design projects that had a larger impact on the community. To accelerate our opportunities to work in that kind of environment, we took on a project locally that we conceived of ourselves, and just thought, “Let’s take on a project and pursue it within the office as a way of exercising our interests,” without any understanding of where that might go.

Q: Which project was this?

JP: An open space project for the South of Market neighborhood here in San Francisco. In the simplest of terms, it was at our doorstep. South of Market is a light industrial area of the city moving to mixed use. And like other cities in this country, these areas lack some of the urban amenities that other parts of the city enjoy, especially recreational open space.

We posed a simple question: if we added this to this urban fabric, what would that solution look like? Our proposed solution ended up capturing the attention of many people within the city, including several city agencies that encouraged us to pursue the project, which is ongoing as we speak.

This led to the larger question: why aren’t architects in this role more frequently, where we’re actually going out in our communities, using our skills and expertise to identify problems in our communities, and then proposing solutions to those problems that may be overlooked by other forces?

Q: So often something important begins with looking at what is right in front of you. You just have to take the first step. So when did the 1% Solution come into being, and why 1%, as opposed to 5% or 10%?

JC: One percent is more symbolic than anything. It’s a small number by itself. However, if you put together lots of 1% offerings or donations from firms, it adds up significantly. If every architecture professional in the country were to pledge this 1% of their time, it would effectively be creating a 2,500-person firm – the equivalent of an HOK, for example – working full-time for the public good. That equates to about five million hours annually, and we think that there’s a lot you can do with that.

Q: What has the response been?

JC: Very positive. The pent-up interest that John experienced in his own firm is everywhere. We’ve now recruited nearly 500 architecture and design firms, ranging from sole practitioners to some of the largest firms in the country. Together, they have pledged on the order of about 200,000 hours to date. If you put even a conservative value of $100 per hour on those, that’s about $20 million right there that the profession is offering to the public on a pro bono basis annually.

JP: The figures that John is talking about are only for the architecture profession. We are in the process of expanding the community of participants within the 1% Solution to other design professionals and to manufacturers.

Q: What are some of the other projects that Public Architecture is pursuing right now?

JC: Our mandate is that we pursue projects on a proactive basis – we initiate projects. This includes our Day Labor Station design initiative, which is one of our most significant and also one of our most politically charged projects. We also continue to advance our Accessory Dwelling Unit – granny flat or in-law unit – initiative.

More recently, with the support of a grant from the U.S. Green Building Council, we have united our various projects – like ScrapHouse, like the community center that we’re involved with up in Seattle – around this idea of material reuse. The idea is to show, through example, how scrap and salvage material can be integrated into new construction at a much greater scale than it is right now. We see that type of project as a campaign that people can contribute to and become a part of. While we are involved with specific projects, we are working to get people involved in their projects.

Rendering of Day Laborer station

The ScrapHouse in San Francisco’s Civic Center

Q: Why don’t you expand on that and talk about some of the other big goals for Public Architecture?

JP: The big goal for the work that Public Architecture is doing is to institutionalize the kind of public service activities that John is talking about. They should be part of an annual effort, part of the business model, part of a routine understanding of practice, just as it is in the legal profession.

Q: Back when you started Public Architecture in 2002, that made sense, but what about now when we are looking at the worst economic downturn since the depression of the 1930s?

JC: The current economy will continue to impact us. The first and probably the most important way is that we’ve seen an increase in the number of firms that are pledging their time, and we see that as a very encouraging thing, because they’re hopefully turning to pro bono work to help weather the down times. Rather than fall back on design competitions or some other outlet, they realize they can fill the available staff time with a project that ultimately might mean a great deal to them.

JP: It may be counterintuitive to think that in a slow economy one would give one’s time away, but we believe deeply that this is exactly the time when one should be taking pro bono work very seriously. As John’s already pointed out, it’s an opportunity to find meaningful work for staff in a turbulent, changing environment, but it’s also an opportunity to distinguish yourself as an organization and to find new avenues to express the good work that you’re doing.

This is the time for firms to be thinking about how they can wisely give of their time to their communities. And when I say “wisely,” it’s to be selective, to set high expectations, both for the outcomes of the organizations or efforts that they serve and for the outcomes that happen within their own firms.

Q: You mean understand how to exploit the benefits of volunteering?

JC: Let’s look at lawyers for a moment. They are generally thought of as better businesspeople than we are. While their fees are probably three times ours, they have a real culture of pro bono that starts in school and goes all the way through one’s career. And it’s not without great benefit to the profession and to these law firms. These firms distinguish themselves to potential employees and to potential clients based on their pro bono work. Otherwise, a lot of those law firms, in the same way a lot of our architecture and design firms do, start looking alike. This is a way that they’ve come to distinguish themselves.

State bars have unique programs that mobilize attorneys in times of crisis, in times of disaster, and in times of political uncertainty – in any number of settings – and what those state bars have also done is use these programs as leverage with their legislatures. When they go to seek changes to their practice acts or whatever it may be, they are able to point to real numbers and talk about the contributions that attorneys are making.

There are plenty more jokes about attorneys than there are about designers, but there is also an understanding that when you need legal representation, you can get it in this country. There is nothing comparable supporting the right to design – supporting the right even to shelter – and so we see all that as related. The ultimate ambition is that design becomes recognized as a right as opposed to the privilege that it is today.

JP: We say right up front that pro bono needs to be a balanced activity. As philanthropic as a firm wants to be, they need to balance that with a return to their organization, so that they’re able to fully utilize the effort that they can give. This needs to be a smart business choice. It needs to be both selfish and selfless.

Q: Simultaneously?

JP: Yes. I think that’s hard for folks to grasp at first.

Q: Can you give us an example of that?

JP: Let’s say that a design firm has done a lot of work to advance the efforts of a nonprofit organization in their community. Can they use that in a marketing environment where they can actually get exposure, help to separate themselves from other design firms, which might lead to paying jobs? Of course. Internally, their service can also lead to a better corporate culture. It can help attract better employees and retain those employees.

We believe that firms need to look at the investment they’re making and think about the return on that investment for a simple reason: their investment will increase when they understand the return that they can get from it. But they have to be diligent about it; they have to be proactive about it. They can’t be lazy about the way that they take in their pro bono work, which is primarily how the design profession has been.

Q: So this is a major sort of shift in thinking?

JC: That’s right. We’re talking about raising expectations across the board. Raising expectations within the firm about the design quality, about the way that the project’s managed and executed and delivered. Also raising the expectations on the part of the clients. An equal component of the 1% Solution is to inform and really get clients excited about these projects and to have them be as demanding as a typical client.

JP: We want to maintain the good-heartedness of the design profession but get design professionals to appreciate the value of taking a business look at their pro bono efforts. You see, if it becomes integral, I think design itself will be more valued.

JC: Our goal is not to make the profession a livelier place to work; our goal is to have an impact on our communities. We’re using the tool of design, and that’s really at the very core of our work.

JP: We need to be building efforts that go way beyond Public Architecture. We’re a catalyst, not the end mechanism, for change. We’re just a catalyst to wake the sleeping giant of the design community towards changing our communities for the better.

Small actions, organized or unified, really create the change in the world. It is powerful for people to realize this – to accept that 20 hours a year just within architecture can equal the strength of the largest firm in the country, and that, as employees, they are agents of change. They are agents within potentially the most powerful, impactful firm that this country can produce.

And I think if you can get your head around that, if you can accept that, I just think the ability of design can be expressed in a way that we have not seen before.