Nothing Too Precious

The Nakashima Studio in New Hope, PA

Most folks disdain New Jersey, but I love the area around Princeton that bathes you in varied green light—just before the summer heat sticks. We crossed the Delaware (and the state line) where Washington did and drove up along the river towards New Hope, Pennsylvania. This strange town mixes up choppers, queers, and candle shops. Turn left on Aquetong Road, and up the hill there is a little sign that says, “Nakashima, Open Saturdays Only, 1:00 to 4:30.” This is where woodworker/furniture maker/architect George Nakashima lived and worked from the mid-1940s until his death in 1990.

As soon as we turned in the drive, I felt at home. Besides the sound of leaves and the changing light, there is something in the air. I was reminded of the Tassajara Zen Center in the mountains behind Big Sur. Maybe it is Japanese culture filtered through a western sieve with a mix of other spiritual teas. A seriousness that is not leaden.

The view from the porch of the showroom building.

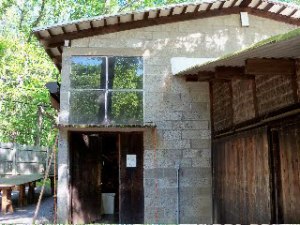

Thankfully, there were not many people, as it was just three quarters of an hour before closing. On non-tour days, visitors can explore four buildings: the showroom, the finishing building, the chair department, and the Conoid Studio.

In the showroom, Nakashima’s daughter-in-law Soomi is voluble but gauges her response by your attentiveness. Although I am interested in the furniture, I am more interested in the space, what it feels like. She tells you as much about Nakashima as you want to know. The furniture and the space between the pieces tell you the rest. Although the furniture is displayed beautifully, it is also casual. This is not a museum. Everything has a job to do. Nakashima expected his furniture to get scratched or dented. Nothing was too precious.

Nakashima combined European modernism, a Japanese aesthetic, a shaker sensibility, and again, something I can’t put my finger on. This is true in his buildings as well as his furniture.

Between the Chair Department and the Conoid Studio

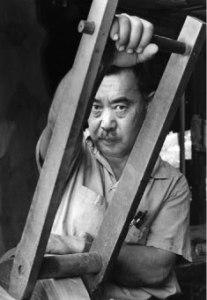

The Nakashima brand seems based on the simple photograph of him as a Japanese woodworker crafting alone in the Pennsylvania woods. But this is far from the truth. He was born in Seattle and received his B. Arch from the University of Washington in Seattle and his M. Arch from MIT. He went to work for the Czech architect Antonin Raymond in Japan, where Raymond had gone to work on Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel and stayed to set up his own practice. Both left Japan before the war, and Nakashima ended up in an internment camp.

Raymond was able to sponsor him so he could leave and move to New Hope. And there he began to make furniture. He had a large team of skilled craftsmen helping. There is an entrepreneurial side of this tale that is also typically American. Americans love stories about foreigners overcoming obstacles, even if the foreigners aren’t really so foreign at all. But the piece of the story that eludes the casual visitor can probably be found, at least partially, in Nakashima’s own story as a seeker who happened to be an architect, not a furniture designer and maker.

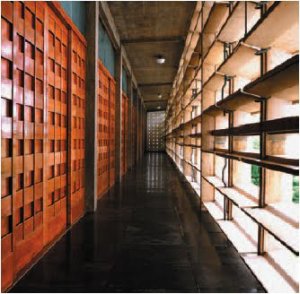

Dormitory for the Sri Aurobindo Ashram

A key part of Nakashima’s story takes place in 1937, when he went from Japan to Pondicherry, India, as Raymond’s project architect to supervise the construction of a dormitory for the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. Golconde, as the building was known, was one of the first reinforced concrete structures in India and would become an important structure in the history of modernism in India. Given the ashram’s ideas and the scarcity of materials, it is not a typical project. What probably changed Nakashima’s path is his interest in Sri Aurobindo’s faith. In her fine biography of her father, Mira Nakashima (named for Mother Mira, Aurbindo’s disciple) writes, “Sri Aurobindo and Mother Mira taught that beauty is the expression of design truth, that freedom fosters creativity, and that focus develops discipline. They also taught that spiritual purity manifests itself in art, an expression of the divine and of the multi-faceted, ultimate truth.” She goes on to write, “Work for him was a spiritual calling, a linking of his strength to a transcendent force, a surrender to the divine, a form of prayer.” Standing quietly overlooking the landscape of the Nakashima Studio, you can almost feel that. I’ve been looking for that sort of clarity with these explorations.

You may be interested in the following websites:

www.nakashimawoodworker.com

www.sriaurobindoashram.org

And the following books:

Nature Form and Spirit: The Life and Legacy of George Nakashima by Mira Nakashima. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2003.

Golconde: The Introduction of Modernism in India by Pankaj vir Gupta, Christine Mueller, and Cyrus Samii. New Delhi: Urban Crayon, 2010.