Elaine Kollins Sewell Jones, Hon. AIA

1917-2010

Elaine Kollins Sewell Jones, Hon. AIA, passed away last month in Los Angeles after being in failing health for several years. I have a hard time expressing what she meant to me as a friend and mentor. Over the last few weeks, I’ve been trying to put a few memories into some order.

I met Elaine Sewell Jones at a workshop for architectural librarians at the San Francisco AIA Convention in 1985. At first, she seemed shy and feminine in an old-fashioned way, but she proceeded to ask me directly for advice on organizing the archives of her late husband, A. Quincy Jones, FAIA.

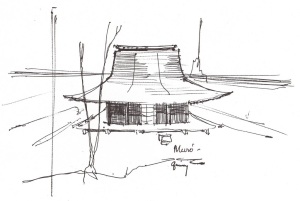

Jones was known for his Eichler homes, but he also created important custom residences, churches, factories, and campus buildings. He wasn’t a specialist—he believed in the idea of the architect as a generalist. There was little I had to offer Elaine at the moment I met her. But she saw something I didn’t. She was remarkable for living in the present, celebrating the past, yet nurturing the future.

She gave me her card; it was unlike any I had ever received. Smaller, more delicate, similar in size to a Japanese business card. I paper-clipped it to my copy of A. Quincy Jones: The Oneness of Architecture, published by PROCESS. Her card told me that she was a communications consultant. I wasn’t even sure what that meant. Yet I remember thinking, “One day I will want to call her.” Within a few years, I was no longer an architectural librarian but an architectural publicist, and the firm I worked for was opening an office in Los Angeles. Quite boldly, I contacted her and asked if we could meet again. I was surprised that she remembered me. Later on, I would learn that she rarely forgot meeting anybody. What I had mistaken for shyness was actually her way of creating space for herself. She was always sincere but kept a buffer zone around her until she knew you and let you in. If people proved themselves, she called them “the good goods.”

When I moved to Los Angeles in 1989, I suggested that she allow me to interview her for L.A. Architect, the newspaper of the AIA Los Angeles chapter that Barbara Goldstein and later Noel Millea edited. For some reason, Elaine agreed. Although she was quoted in several books, articles, and documentaries, I don’t think she ever agreed to another full-length interview. (The interview is reproduced here.) In the 1990s, I suggested a few times that she agree to an oral history with UCLA, to which she was donating Quincy’s archives, but she would gently steer the conversation in a different direction. She created a process through which architecture and design could be understood and appreciated. She never wanted to be perceived as self-serving. Unlike most people, she didn’t need recognition. Our mutual friend Katherine Rinne told me that many of the unsigned articles in Arts+Architecture magazine were actually penned by Elaine.

During our many conversations, I asked her questions about some of her clients, including her work with the Herman Miller Corporation and with Charles Eames, Alexander Girard, and George Nelson. She was good at deflecting. As we got to know each other better, she would tell me a few things about Charles or Ray Eames, but never anything that would contradict her professional relationship with them. She told me once about taking a trip to Carmel with Ray. During the day, they went their separate ways and connected again in the late afternoon. They had both purchased a piece of ribbon—the same exact ribbon. She saw what her clients saw. We talked about creative people being self-centered, but she meant it as a compliment. They knew where they were going. She could be elliptical at times, but she also believed in facts. She didn’t like it when people got their facts wrong or mistook a speculation or opinion for the truth. This would happen a lot as people began to try and parse the Eames relationship. Her response about those people was clear: “They weren’t there.”

In 1990, UCLA Extension asked her to talk about her husband’s work as part of a lecture and tour. She felt that would be too self-serving, and she suggested two young people interested in Quincy’s work instead: Maggie Valentine, an architectural history student at UCLA who later wrote a book on the architect, S. Charles Lee, and me. I had no real idea what I was doing, but I was driven by an interest in modernism and the challenge of preparing a lecture. For months, I spent every Friday afternoon at The Barn, the home in Century City that she shared with Quincy, going through materials trying to understand his oeuvre. Elaine never asked to see an outline or intervened except once when I had chosen a slide because the chemical change over time gave it an extra nostalgic punch. She promptly suggested a replacement. If the work was interesting why be false?

After I moved back to the Bay Area, I would try to visit her at The Barn in Los Angeles between meal times so she wouldn’t go to the trouble of preparing a meal. But still there was tea and it was always exquisitely presented in the large square table overlooking the courtyard. Even drinks would be accompanied by a beautifully arrayed choice of morsels. Beauty could not be compromised or contained.

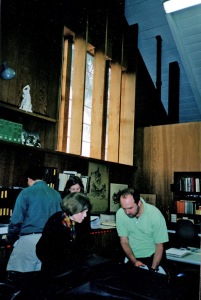

The studio at The Barn where Quincy taught 5th year students. Later it was one of the spaces where Elaine processed the archives. Photo courtesy of Lauren Bon and Metabolic Studio.

In the late 1990s, I received a call from a young man named Michael Blackford, who said that Elaine suggested he contact me. He was trying to save one of Quincy’s few projects in Northern California (besides the Eichler tracts), the Daphne Mortuary. Bridge Housing had bought the parcel from the Daphne family and wanted to replace it with affordable housing, a noble enough goal. Elaine understood from the outset that the dialog about saving the building was worth having, whether or not the building was actually preserved. If she got directly involved, it would be, again, too self-serving. Perhaps a more creative architect than the one Bridge hired could have figured out how to use the building and its ideas in the new scheme. The publicity resulting from the fight to save the Daphne was not about NIMBYism as Bridge first suggested, but about reassessing the architectural legacy of modernism. For better or worse, the process worked, even if the individual building wasn’t saved. Afterwords, Elaine always referred to it as the Daphne caper. Although her work had everything to do with the physical world she also understood that it was transient. Love was permanent.

Elaine never criticized religious traditions. I didn’t know her to practice any specific faith, although she certainly had a strong reverence for Japan. Yet she was the most compassionate person I knew. She treated every person with the same respect and generosity no matter what their line of work was. If someone proved untruthful or unkind, she subtly distanced herself. She was always moving toward kindness.

PreColombian artifact on Alexander Girard fabric

Maintaining hundreds of friendships, processing the archive, meeting scholars and students, and trying to take care of The Barn took up incredible amounts of time. She only slept a few hours a night. Sometime in the early evening, her watch would make a sweet ringing sound, which was a reminder for her to eat something. She would just go on working. The challenge of being Elaine’s friend was meeting The Standard. I always worried whether anything I did would approach her level of excellence and thoroughness. One day, we were discussing marketing and communications. I was using the terms interchangeably, and she focused in on the two words. Her point of view, which I came to adopt, was that communications was the umbrella. Marketing was somewhere beneath it. She didn’t correct me; she engaged. She never wavered in her focus on the individual or their work. No detail was too small to look at again.

This way of being must have been with Elaine from an early age. She graduated from Oregon State University in 1941. She moved to Kansas for a time and from there co-edited a newspaper during World War II called the Oregon State Yank that consisted of letters from fellow students who had become soldiers. The many letters ended up with her, and she would eventually catalog them all with great care and give them to the university in 1991. What could have been lost to history became one of the most significant archives in the country documenting the day-to-day wartime experiences of soldiers during the war. If she took on a job, she did it right.

Although we went to dinner a number of times, we rarely attended a cultural event together. But we both went to the opening of Blueprints for Modern Living: History and Legacy of the Case Study Houses in 1989. I was at the beginning of my career, and she was the doyenne of the modernist moment in Los Angeles. I feel that show (and catalog) was a catalyst for the resurgence of an interest in midcentury modernism that probably led to a reappraisal of Quincy’s work. For part of the evening, we toured the museum together with Lucia Eames. Standing in the reproduction of her father’s living room I said nothing, just absorbed in the brilliance surrounding me. Elaine and Lucia chuckled together over Saul Steinberg’s drawing on an Eames fiberglass chair. I couldn’t believe my good fortune to just be there.

The Eames living room reconstructed in the Case Study House exhibit at MOCA

Photo courtesy Museum of Contemporary ArtIt took me several years to understand that Elaine had probably hoped that my interest in Quincy’s work would blossom into a book. But we were different in a fundamental way. In addition to having great discipline, she was fearless and had an inner strength that would allow her to face any adversity. She would stay calm, solicit opinions, and make a decision. I followed my passion, but not quite beyond my fears. If she was disappointed that I didn’t pursue that project, she didn’t show it. Whenever I sent her writings or clippings, she was always encouraging.

In June 1999, I brought several friends from Northern California on a tour of Los Angeles, which culminated in a visit to The Barn. As always, she was prepared. She showed all of us around, gave everybody a PROCESS book, and joined us for dinner. She wanted to be around young people and hear what they were thinking and designing. She shared her home with thousands of people and it is hard to think of it without her being there physically. Thankfully, Lauren Bon and Metabolic Studio, a direct charitable activity of the Annenberg foundation, has purchased it. Fred Fisher, the thoughtful architect who purchased Quincy’s office building, is renovating the building.

Until she couldn’t type anymore, she was the most faithful correspondent I’ve ever known. I have dozens and dozens of her letters. A number of years ago, I knew that her arthritis and carpal tunnel syndrome had worsened, and she seemed to be aging quickly. We came down, stayed nearby at the Century Plaza, and spent most of an afternoon reminiscing. When it was time to say goodbye, she walked us to the car to get our parking permit, and I turned to watch her walk down the hill back to the porch. Her beautiful skirt fluttered in the wind. I saw a young woman nearly skip back to work.