A few years ago, my friend the architect and NorCalMod author Pierluigi Serraino took me to see a house designed by Don Knorr with interiors by Alexander Girard. It was almost perfectly intact despite being 40 years old. Girard’s exuberance fit perfectly into a timber Miesian dwelling. We suggested that it might make a great story for Interior Design. A few months later, Eric Laignel photographed the project, and Edie Cohen authored the article. You can see it here at http://www.interiordesign.net/article/484672-Welcome_to_1969_pix.php?intref=sr.

(For the online version of the issue, Pierluigi and I had our own conversation, which you can see here: http://www.interiordesign.net/article/483940-Conversations_with_Pierluigi_Serraino.php?intref=sr)

|

| Front doors designed by Alexander Girard Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

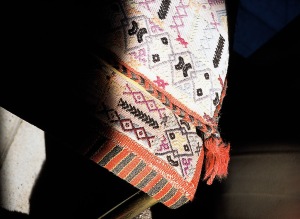

More than 20 years ago, I visited the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe and was dazzled by Girard’s collection and display. When I lived in Los Angeles, my friend Elaine Jones gave me a few samples from the years she worked with Girard, George Nelson, and Charles Eames at Herman Miller. These little pieces of fabric are among my favorite mementos.

But somehow I missed the exhibit at SFMOMA in 2006–2007. Recently I was having lunch with Ruth Keffer and found out that she was involved in the show. Looking for any excuse to talk about Girard, I asked her some questions. Her answers give us some further insight into the legendary designer.

|

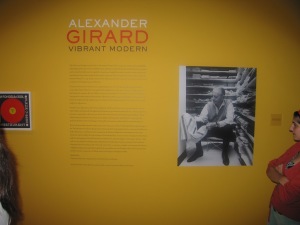

| Girard exhibit entry Photo: Ruth Keffer |

|

| Entry sign on freight elevator Photo: Ruth Keffer |

Q: What was your role in the Girard exhibit?

I was the curator. That role fell to me because Joe Rosa [SFMOMA’s curator of architecture and design] had decided to move to the Art Institute of Chicago in 2005, so his exit timing became my opportunity. Most of the pieces in the show were accessioned by Joe, except for the Three Passenger Sofa and the La Fonda Chair, which the museum had acquired during the Paolo Polledri era. The pieces that Joe accessioned all came from one donor, a local collector named Carl James, who had been the manager of the Herman Miller showroom in San Francisco back in the day. Carl had lots of textiles, obviously, and many pieces from the La Fonda del Sol restaurant in New York, and a cache of ephemera that mostly wasn’t in the show but resides in SFMOMA’s library archive.

The exhibition was intended as a showcase of that accession, with a few other pieces thrown in. It was small, but there was enough for me to create what I felt was a meaningful survey of the high points of Girard’s career: Herman Miller and the textiles, the work for Braniff Airlines, La Fonda, and a smattering of graphic design.

|

| Girard patterns Photo: Ruth Keffer |

|

| Girard exhibit title wall Photo: Ruth Keffer |

|

| Girard exhibit gallery Photo: Ruth Keffer |

|

| Gallery exhibit detail Photo: Ruth Keffer |

Q: Did you know about Girard before you started working on the exhibit?

More or less. Mostly less. I think I lumped him in with the other biggies of midcentury design. I knew more about Herman Miller in general than I did him. When the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum did their show in 2000, I remember being very excited to see the images from that exhibition (although I never got to see the show itself), because I’m a huge textile fanatic. But I was still not processing who he was in relation to the company or to Eames and Nelson, or his real stature as a designer. And it’s funny, because I think my confusion had something to do with the way we think of textile designers as a step or two below furniture designers, who are a step or two below proper interior designers, who are a step below architects.

|

| Photo: Ruth Keffer |

|

| Photo: Ruth Keffer |

|

| Fabrics with three passenger sofa Photo: Ruth Keffer |

|

| Three passenger sofa with pillow Photo: Ruth Keffer |

Q: Had you been to Santa Fe to see the Museum of International Folk Art?

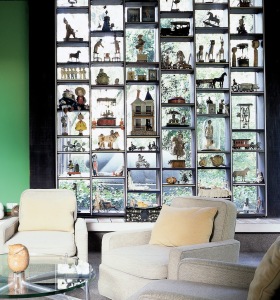

I had not and have not seen the MoIFA. But I have studied Girard’s work there—the layout of the collection, the contents of the collection, his philosophy of taxonomizing things, etc. And that is where I run into trouble with my easy analysis of Girard, for as much as one can rhapsodize about the extraordinary innovation of his textile designs, when it came to his relationship to folk art itself, to the objects that inspired him as a collector and an artist, he was rather formalist. Or should I say, strictly formalist. He had no interest in cultural anthropology. No interest in folk art as a domain of academic inquiry, and likely no awareness of questions about appropriation or imperialism or any such thing. Up until I started looking at the MoIFA work, I had been thinking of him rather breezily as the father of postmodern design, the first to embrace non-Western influences and celebrate outsider art. But now I’m inclined to think he really didn’t have that kind of vision. What I do think is that as an artist he had a keen attraction to and a sensibility for other artists’ work, for their craft, their color sense, for their own joy present in the objects they created. And I think that’s what made him such an obsessive collector. (Truly obsessive!) And it’s no wonder that toys were his principal passion as a collector.

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

Q: Even if Girard didn’t have an interest in the larger philosophical or political aspects of collecting, don’t you think he saw cultural threads?

Definitely he saw cultural threads. I think he was always looking for, and firmly believed in, the idea of cultural commonalities, of the Family of Man. One of those commonalities is the idea that physical objects are vessels for memory and feeling. Girard thought this was a crucial idea to remember and incorporate when designing a space, but he thought that modernism, as a design agenda, had left this notion behind, to its detriment. Ironically, modernism was looking for a way to be global and cross-cultural, but by being abstract. So it’s effacing all those elements that have culture-specific, or what could be defined as narrative, references. But for Girard, storytelling was the whole point, since it is the core activity of every culture. Design is storytelling, and design elements—whether objects or motifs—are dramatic players in the “theater” that one creates when designing.

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

I got very excited by this idea when studying Girard, because it’s the same rhetoric that Kandinsky used when describing his compositions and his relationship to the elements in his work. It is formalism, but it’s not superficial or lacking in political relevance, as the academics would argue. It’s a search for, and a celebration of, something deeper and more immediately human. In the case of Girard’s geometric patterns, the forms are not really abstract but abstract-ed—each adapted from their original context to serve a specific two- or three-dimensional design context, such as the folds of a curtain or the contours of a chair. So the feathers on the surface of an Incan ceremonial cloak become the repeating pattern of the 1957 “Feathers” textile, and in each case the feathers are both a formal and a narrative element, wielded deliberately by the artist for evocative purposes.

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

Q: Do you think that George Nelson ends up raising Girard and thus other textile designers to a much higher level of appreciation?

It’s really hard to say when this happened or if it really happened at that time. It’s true that Eames and Nelson and other designers who worked with Girard spoke openly about their reverence for him—he was considered the true genius with instincts they envied. He was prolific and aggressive and very confident. (At one point he was also called a “design automaton.”) And he embodied the Bauhaus principle of the Gesamtkunstwerk, creating the total design environment as an architect, interior designer, and textile designer.

|

| Photo: Ruth Keffer |

|

| Photo: Ruth Keffer |

Q: Do you feel that you got to show that sense of the Gesamtkunstwerk in the exhibit at SFMOMA?

I certainly tried to, though it was a challenge given the limited number of pieces we had to show. But I thought I touched on his holistic approach in each of the various projects: the way the Herman Miller textiles work with the furniture; the idea of a totally branded environment for Braniff; and for La Fonda del Sol, a complete design package: graphics, tableware, fixtures, the space and light of the interior.

|

| Photo: Ruth Keffer |

|

| Checkerboard cloth Photo: Ruth Keffer |

|

| La Fonda del Sol tableware Photo: Ruth Keffer |

Q: Girard has been getting a fair amount of attention these last few years. But his works were not always popular?

In the 1950s and through the Kennedy era, his patterns did not sell well. He could not convince Herman Miller customers to surround themselves with cheerful, playful patterns at the same time they were purchasing minimalist furniture. The Textiles and Objects store—where Herman Miller sold folk art objects alongside the textiles—was a failure.

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine Front door detail |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

By the time he left Herman Miller in 1973, though, the situation had shifted. The hippie culture embraced non-Western influences, and Pop artists had been doing their thing, and Girard started to look prescient. Designers who followed Girard’s lead in borrowing motifs from other cultures were selling, and they were getting attention as designers. But I think Girard recognized that this new trend, and the growing celebrity of designers in the mainstream culture, had everything to do with marketing and the search for novelty and little to do with his heartfelt quest to plumb the mysteries of the human condition. He remarked, in an interview in 1974 with the curators of a Herman Miller show at the Walker Art Center, that he had recently gone into a Miller showroom in New York and been dismayed by what he saw, or didn’t see, there. He said, “There’s no more religion.”

|

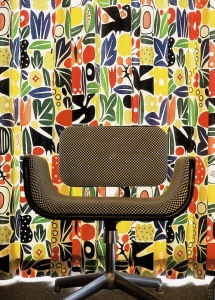

| Girard chair in front of Girard fabric Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

|

| Photo by Eric Laignel courtesy Interior Design magazine |

Which I think reveals the way in which Girard truly was a modernist himself — he believed that design should serve the greater good.

Photographer Eric Laignel and Interior Design editor in chief Cindy Allen graciously loaned the photos from the story that ran in Interior Design.

For more info:

www.ruthkefferdesign.com

www.ericlaignel.com

www.maximodesign.com/

girard.houseind.com/

www.internationalfolkart.org/about/girard.html

www.interiordesign.net

|

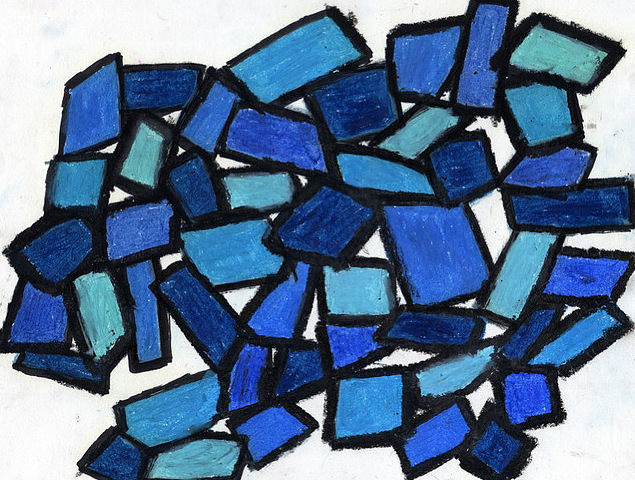

| One of Keffer’s digital patterns |